Developed in 1994 and published the following year, Chop Suey was a cunning piece of multimedia edutainment, suited just as well to grown-ups — smirking hipsters and punk rockers, probably — as it was to the prescribed “girls 7 to 12” crowd.

But it wasn’t a computer game. It was something else: a loosely-strung system of vignettes; a psychedelic exercise in “let’s-pretend”; a daydream in which the mundanity of smalltown Ohio collides with the interior lives of its two young protagonists.

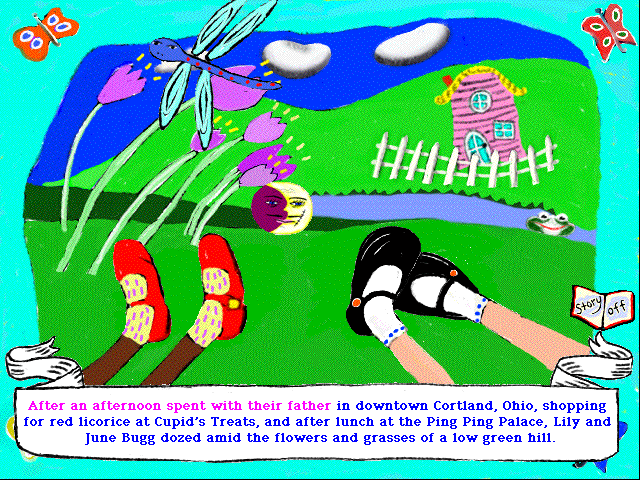

As the game opens, the Bugg sisters are idling on a grassy knoll, counting clouds and recalling the day’s events. Lily and June Bugg, we are informed, have spent the afternoon with Aunt Vera. The narrator — a yet-unknown David Sedaris — sets the scene in nasally twee, occasionally grating reeds.

“They didn’t know the names of the flowers in which they lay — pollen dusty daisies, wild violets, cornflowers — so June Bugg named them herself, touching a finger to the soft center of each.”

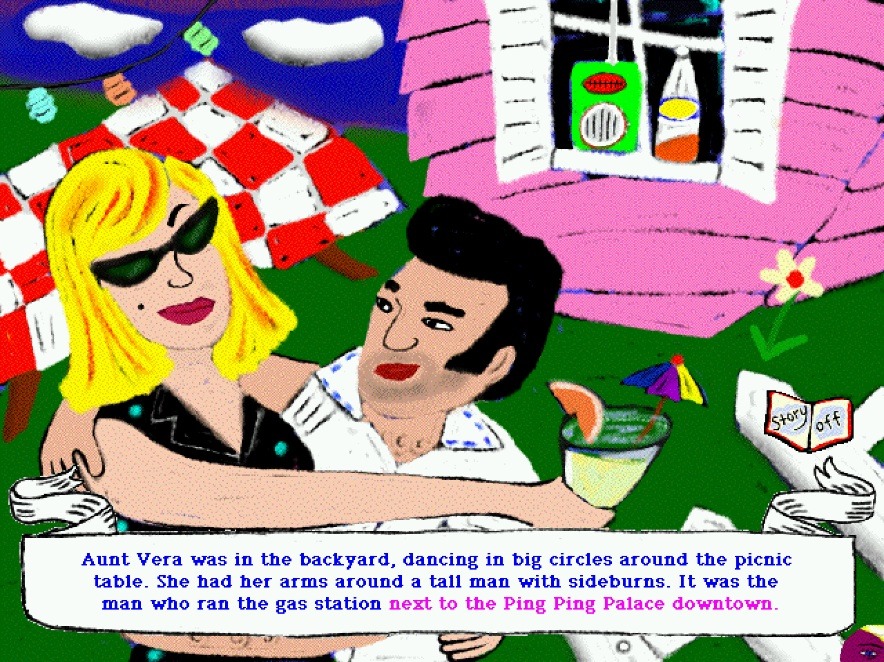

When Sedaris concludes his opening narration, our player immediately regains control of her cursor. From here she can survey Cortland’s landmarks in any order she chooses, repeating anything she likes. She might revisit lunch at the Ping Ping Palace, where the food is so exotic, it’s often tinted cyan or hot pink. She might play dress-up with Aunt Vera — whom, we suspect, is something of a lush and a man-eater.

. . . Lily and June’s own imaginations illustrate those stories in happier, more magical idioms

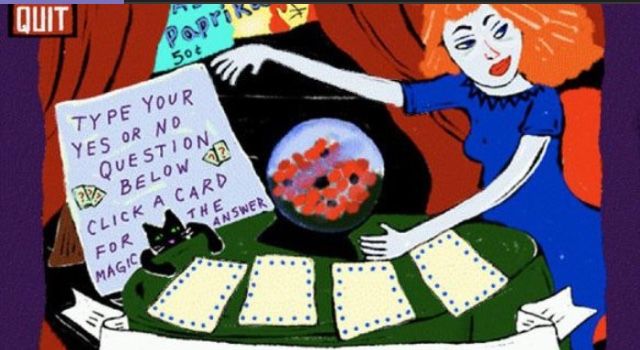

The player might go to the carnival to have her fortune read; she might play Bingo. Perhaps she might visit Aunt Vera’s second husband, Bob, or else she could visit Vera’s third husband, also Bob. (Tragically, it is impossible to visit Bob #1, except through occasional flashbacks.)

“‘A broken heart for every light,’ she said, and sighed, rearranging her pink flowered bathrobe.”

Most in-game stories are delivered secondhand from a reminiscing grown-up, while Lily and June’s own imaginations illustrate those stories in happier, more magical idioms. The game never oversteps, never makes “regret” its central concern; after all, this is a children’s game. But an adult player might be surprised at how wistful the game actually is.

Wry flourishes give Chop Suey its teeth: Dooner, an unemployed Gen-X slob, hides his girly mag in the dresser’s top drawer. And if our player puts on a pair of X-Ray Spex, Aunt Vera and boyfriend Ned are both reduced, tastefully, to their undergarments.

Were Chop Suey a literal, physical picturebook, it might resemble Richard Scarry’s Busytown as revised by Bratmobile. Alternatively, we might go along with Entertainment Weekly‘s description: “a little like Alice in Wonderland as performed by the B-52s for NPR.” (The magazine went on to name Chop Suey 1995’s CD-ROM of the Year.)

Chop Suey‘s nearest analog, though, is a very different edutainment title, Cosmology of Kyoto. Released the same year as Chop Suey, Kyoto is another interactive storybook designed to make good on the early-’90s’ promise of CD-based “multimedia.” But Kyoto is technically limited by Macromedia: the game itself feels strangely static, and while there’s lots to explore, there’s little to do.

Chop Suey suffers these failings and worse. All told, it takes only an hour to see everything in the game once, and then there is little incentive to play again, except to remember how the game went. The player can’t “save” her “progress,” because there is no such thing as progress. In 1995 at least one reviewer worried Chop Suey might frustrate children with its circular narrative.

Every moment in the game, however connected, is also suspended in time

But the game’s perpetual loop of story is deliberate: “It works the same way that Alice in Wonderland does, where she leaves home and then she has adventures,” designer Theresa Duncan explained in 1998, “but if you took everything in between the beginning and the end of Alice in Wonderland and scrambled up every chapter, it would make no difference to the development of the story.” Every moment in the game, however connected, is also suspended in time.

In an industry glutted by worthless “games” for “girls” — the mid ’90s begat a tide of titles like McKenzie & Co., Let’s Talk About Me!, and Barbie Fashion Designer — Chop Suey really did get it right.

Wired‘s Greg Beato was certainly impressed. “With its sly whimsy and tactile, folk-art imagery,” Beato writes, “Chop Suey brings a whole new sensibility — quirky, poetic, almost bittersweet — to a medium that’s often lacking in such nuance.”

The game’s visual charm owes no small debt to collaborator Monica Lynn Gesue, whose handmade art is at once childlike and sophisticated. Every screen is a frenetic hodgepodge; every animated painting, all squiggles and loop-de-loops.

Nevertheless, Chop Suey‘s main star was Theresa Duncan, whose competence as a game designer inspired a flurry of magazine profiles. But Duncan was celebrated as much for her audacious wardrobe as she was for her intellect. Salon, in 1998, called her “a predatory businesswoman,” taking extra care to note how well-dressed she was. In a 2000 issue of Shift Magazine she was heralded “Silicon Valley’s It Girl”; this proclamation was accompanied by a photo spread. Paper profiled Duncan as well: “Theresa wears a top by Ashley Pearce.”

In a 1997 issue of Bitch Magazine, Doreen Hinton — who presumably had never seen a glamor shot of Duncan — succeeded in praising Chop Suey itself, saying, “This is the least gender-specific game of all the ones labeled ‘for girls’ by marketers and writers.”

Indeed, where many developers were briefly, madly obsessed with giving pre-teen girls their own tier of games, Chop Suey‘s real accomplishment was that it seemingly targeted nobody. It’s “feminist,” albeit in a 1990s way: subtly, subversively. Not so long ago, girls’ books, girls’ music, and girls’ games demanded to be taken as seriously as the boys’, simply by being better than the boys’ stuff. A ’90s kid could opt to trade Sweet Valley High for Weetzie Bat or a Blake Nelson novel, say.

“[Duncan is] clearly the one to watch among developers of any gender,” Hinton’s article continued. “I can’t wait to see and hear and play her next offering.”

But Theresa Duncan managed only two more games. Smarty (1997) starred an eponymous heroine, Mimi Smartypants, and garnered a fast cult-like following. Zero Zero was released the very same year (“It’s good,” conceded the Associated Press, “but it’s no Chop Suey“).

The Internet has been an unkind documentarian, slowly turning Chop Suey from a “has-been” into a “never-was.”

Why isn’t Chop Suey better remembered?

Even as Duncan struggled to market her next two games independently, the 1990s edutainment craze had staggered to a halt.

Despite all its critical acclaim, it’s tough to say whether Chop Suey ever sold well. Anyway, how could it have? By 1997, when I first started searching for a copy, the disc was completely out of production. (I did eventually find the game, in its original box, eight years later.) Tech journalist Sam Machkovech explains that contemporary educational software has no shelf life: “Edutainment sellers quickly realized families would pass CD-ROMs along to friends once their kids had grown out of them,” he told me, “like used baby clothes.”

Computer gamers, too, had lost patience for so-called interactive fiction. The genre was quaint at best; at worst, adventure games were boring.

In the end, though, the Internet’s memory is not too long. A search for Chop Suey uncovers almost nothing, redirecting instead to endless, looping coverage of Theresa Duncan’s 2007 death — a suicide, and a salacious one at that. Circular narratives really are frustrating, it turns out.

By 2007, 40-year-old Duncan had reinvented herself as a blogger and filmmaker. As a result, most obituaries blithely skim Duncan’s contributions to children’s edutainment. New York Magazine remembers the erstwhile visionary as a “woman spurned by success.” Another article, this one from Vanity Fair, describes a party at which Duncan “dragged out of a closet her old CD-ROMs”: the writer recasts Duncan’s computer games as some ancient football trophy the woman ought to have been embarrassed about. (The article continues, “‘Everybody kind of looked at each other like, Oh no, what is she doing?'”)

When Duncan reappeared in the news cycle, I thought Chop Suey might finally elicit more attention. I was wrong. A terrible, titillating death is far, far more interesting than an author or artist’s creative output.

Theresa Duncan’s death was assuredly a tragedy. But Chop Suey, like Duncan herself, was a critical darling of its time. The slow retcon of Chop Suey into anything less than a towering achievement is, in itself, tragic. The Internet has been an unkind documentarian, slowly turning Chop Suey from a “has-been” into a “never-was.”

In some ways, Chop Suey is very much a product of the ’90s. It banked on that decade’s “girl game” boom. Its soundtrack screams alternative radio. Ornate scribbles and doodles glow as if they were lifted from MTV.

In other ways, Chop Suey is timeless. The technology holds up: the disc runs well, even on the latest computers. Duncan’s writing is still fresh, and Gesue’s artwork seems so alive. I’d venture to say that the game has aged “gracefully,” except that it has barely aged at all. Chop Suey is several perfect moments, suspended — “like shiny-dull pearls on a long, long necklace.”

Above all, Chop Suey was brave. It dared to represent the criminally underrepresented: that is, the wild imagination of some girl aged 7 to 12.

![]() originally published at Vice Motherboard; reprinted with permission by Rhizome

originally published at Vice Motherboard; reprinted with permission by Rhizome