Struggling to Connect in a Pixilated World

The process of estrangement from self and others results from a declining sense of embodiment in social space and an associated diminishing of communication possibilities. …The dementing body is situated temporally and spatially in a known past as opposed to a confusing and incoherent present. From this basis, we can suggest that the not-uncommon ‘behavior’ of the sufferer who ‘wanders’ back to the house of his childhood is a motivated attempt to return to the security of a known ‘habitus.’ The logic of this argument is derived from the superficially self-evident notion that social and individual identities are tied to the body and its location in time and space.

—Christopher King

“Cultural dimensions of dementia and care-giving.” Care-giving in dementia: research and applications, 1997.

I.

“Wow, you must really hate yourself.”

That was Scott, typing at me from three city blocks away.

“What,” I said aloud at my desk.

“WHAT,” I typed back at Scott.

“Jesus, come on,” he typed back. “Is that really what you think you look like?” This was three, maybe four years ago, and yes, I thought it resembled me.

I minimized the chat window and returned to my work. My avatar’s butt was a perfect bubble. She had a gut. Her breasts were wide and low on her torso. I picked at her head with the cursor, trying to squish it. I grew her hair out to her shoulders. I prodded at her dimensions until she was shaped, approximately, like a cheese cube.

Scott had enrolled me in Second Life. We were both living on Pine Street in San Francisco, close to Union Square, so that I could walk in a straight line from my apartment to his. If we were running late to the office in the morning, Scott would ring my doorbell. When we walked to the office together, I always wanted to take the shortest, steepest trip down Grant through Chinatown. Sometimes, if I walked alone to the office, I would get lost. Scott was my glue.

Now he and I were each sitting at our respective desks at home, separated only by a short incline of cement and cable car tracks and a laundromat. We were conducting an experiment.

Pleased with my avatar, I opened the chat window again.

“You’ve made yourself a troll,” Scott had typed.

I thought I looked OK. Then I looked at Scott. It was an uncannily spectacular achievement: Scott looked like Scott.

“I think I need to find myself a pair of glasses,” I told Scott. Scott was wearing glasses.

Default hair, oh my God. That’s how you can instantly pick out a newcomer. And his walk: newcomers wobble gracelessly, like toddlers, because they haven’t learned how to attach animations to their arms and legs. Their skulls clip through their hair in this macabre way because they haven’t yet discovered they can adjust the wigs on their heads. No one in Second Life wants to talk to newbies, anyway. Newbies never last long.

Second Life is a walled no-man’s-land. Its residents endure; visitors, however, soon realize their mistake. Linden Lab has never reported just how many new users log off Second Life forever—most of them within hours, maybe minutes, of registration—but the anecdotal evidence is damning.

“The technology isn’t intuitive,” TIME’s Kristina Dell wrote in 2007, adding, as a parenthetical aside, “I spent my first hour on Second Life wearing both sneakers and high heels because I couldn’t figure out how to discard one pair.”

And while Second Life’s singly inscrutable user interface has been modified since Dell’s experience—forgone is the pie-shaped context menu I learned to loathe—the virtual world’s inaccessibility runs much deeper than shoes.

The problem lies in trying to make yourself look even passably human.

At the outset, it’s easy enough for you, the new user, to understand “wearing” shoes. You understand “wearing” jeans. But it’s harder to understand “wearing” hair, eyes, a body shape, skin. These are basic things you expect to be given directly at birth. Instead, you will begin your Second Life looking stupid, doll-like, and ugly. That’s only because you haven’t learned its secret language. Prims! Parcels! Poseballs! Mouselook! Snap to grid! Attach prim to chin!

Learn a scripting language so your apartment windows will open!

Any well-adjusted person would concede defeat in minutes.

I was sitting at my desk in the office the next day, screwing around on the Internet (because that was my job back then, see), when I heard heavy footsteps stop behind me. I spun around in my plastic rolling chair, spooked.

And there was Scott, all spidery limbs as he propped himself against my cubicle’s frame. He held his paper cup of coffee skyward. He was grinning at me.

“Oh, please don’t say anything,” I begged. “Don’t talk to me. Don’t even look at me.”

I folded my arms across my keyboard and put my face down into them.

“Oh, come on,” he said, “what’s the problem?”

“I don’t know!” I said into my keyboard. “Leave me alone!”

“Okey-dokey.” I heard him tromp away.

“And don’t tell anyone!” I yelled into my forearm.

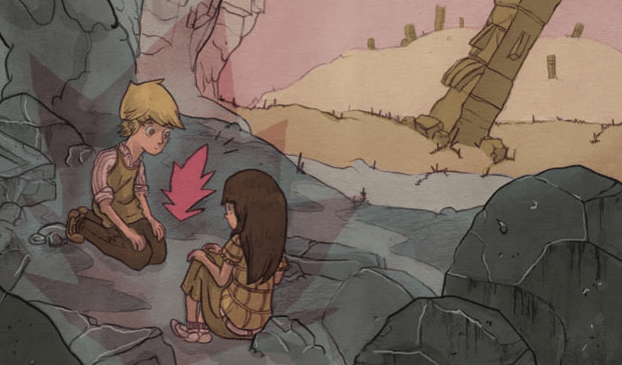

Here is what had happened: after I’d finished my avatar, Scott had taken me to the Wastelands. The Wastelands region, a barren, post-nuclear dystopia, was my whole reason for touring Second Life.

There’s this entire sim, OK, where a simulation is—how did William Gibson define cyberspace? “A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators”—so Scott and I were visiting this user-generated simulation, a place made by not billions but possibly hundreds of Second Life users, all these creators, each with his own tiny patch of land, everybody committed to building burned-out shacks and crooked towers from tin plates and plywood. This aggregated, makeshift adroitness would make any cyberpunk swoon, all these small pieces, loosely joined, culminating in a Mad Max mud flat.

And because these individual aesthetics and minds thrum in concert with one another, they can produce a consummate apiary that is so much more robust and organic and visionary than you could ever find in some movie or video game. A film set or game location is a small-minded thing, just a room in a dollhouse, hamstrung by its one set designer or its one project lead.

So I’d been admiring the Wastelands sim—I had warmed to this work of a hobbyist hive mind, and now I was singing its hymns—when I realized I was dressed all wrong. I mean, really. Who pairs brown roller skates with feathered black angel wings? And jeggings? My avatar was blithely skimming the dunes in the getup of a 15-year-old Slipknot fan.

“Just a second,” I’d typed to Scott. “Don’t go anywhere. I need to take these stupid wings off.”

Then I right-clicked on my avatar’s wings. A context menu, round and shaped like a pie chart, appeared on the screen. I tried to click on the correct wedge of pie.

One stray mouse-click later, my avatar was completely naked. The wings were gone, but I’d managed to vaporize all my clothes along with them, just like that.

“Um,” I typed then. “What happened?”

And then, on the next line,

“Do I look naked to you?”

And then Scott’s reply,

“HA HA HA HA HA.”

I tried to hide myself behind a tree.

“It doesn’t work like that,” Scott typed.

“God! Go away! Stop looking at me!” I fumbled through the onion of menus, feeling around for a shirt, a pair of pants, anything.

The next day at my job, I could not look Scott in the eye.

But I had learned an important lesson. The embarrassing situation can be completely artificial, yet the humiliation is real.

Philip Rosedale was just 31 years old when he dedicated his career to haptics, which is even now a nascent discipline.

Superficially, haptic technology is everywhere. When a PlayStation controller rumbles in your palms, letting you know that your car has exploded, you are benefiting from 50 years of scientific study. When your phone’s touchscreen throbs beneath your finger, reassuring you that you tapped the thing you think you tapped, that tactile feedback is totally haptic.

But Philip Rosedale—Philip Linden, to his fans—had more abstruse aspirations. He wanted to create an environment where visitors could tangibly grope abstractions of objects, could yank or grapple or shunt or hoist or prod three-dimensional masses that weren’t really there but felt like they were. And so in 1999, with his own earnings, the cocksure young entrepreneur founded Linden Lab.

In the beginning, Linden World was formless and empty. The Grid was exclusively a scientist’s sandbox, an experimental soil. In it, primitive geometric shapes, or prims, could all be trussed together into ever-more intricate structures.

This strange terrain was accessed not by a browser, but through a ponderous chunk of hardware Rosedale called “the Rig”. No mere VR headset, the Rig was Rosedale’s prototype, his proof-of-concept, a huge steel cage fitted with monitors and bridled to its bearer’s shoulders and head. Within the ballasts of these marvelous constraints the user became, corporeally, the pivot of Linden World’s interactive panorama.

But the medium is the message and all that, and the Rig wasn’t viably the moneymaker Linden World could be. So Second Life, like penicillin and Teflon before it, is just some happy accident.

In 2008, I finally found the right pair of eyeglasses. I spent a few hundred Linden Dollars on them. (The Linden economy and its exchange rates fluctuate every day, but the U.S. buck remains strong: my eyeglasses cost less than a real-world two-dollar bill.)

The glasses were pricy, as virtual glamour objects go, because so many options are built in. I can change the frames’ shape, or the stems’ color, even the lenses’ transparency, using a series of nested context menus. I can make the eyeglasses very large or very small. It is like owning a hundred pairs of eyeglasses.

Linden Lab, the developers of Second Life, did not design my avatar’s eyeglasses.

Second Life’s inadvertent meaning—its intent, its point, if you demand one—is that this entire feckless reality, from your face to your shoes to the weeds under your feet to the birds in the sky to the freckles on your nose, is a mod. It is all user-generated, an amalgam of other users’ needs. The cigarette you’re smoking came from one person who is likely, in life, a smoker. Your cropped pinstripe pants were made by another guy, because he decided he needed too-short pinstripe pants and made himself a pair. Your hoverboard was designed by this other guy who owns both mattes of Back to the Future Part II on DVD. Your eyeglasses came from this otherother guy who is squinting amaurotically into his monitor at this very second. Your avatar becomes a meaningful hodgepodge of virtual identities lifted from other users. You are not alone.

One day a woman (or seemingly a woman, anyway) sought me out because I had purchased maybe 15 of her skirts. I had blown all of US$5 on her designs, if that. We remained friends for a long time.

II.

When I asked Nikolaus if he wanted to have sex in Second Life with me, he said yes. He and I had been dating, rockily, for five years. He said he missed me.

I was in Texas. I’d been living with my parents for a few months. I was getting scared. I still rented the apartment on Pine Street, and Nikolaus still had a pair of keys to it. He was taking care of my pets and plants. Maybe if he really missed me, he could let himself into the apartment and sit inside. He could even use the Xbox if he wanted. He could read my books. He could use the kitchen, he could use the shower and the toilet.

Sure, he missed me. So he said yes.

I explained that Virtual Amsterdam was a place that couples went, and that I’d—really! Really!—never been there before. But I’d read about it. We could rent a room?

Nikolaus said yes.

I was embarrassed. But even if Nikolaus were lying, even if he didn’t really miss me so much, was our curiosity about virtual sex so aberrant? After all, if countless reports are to be believed, sex is the only thing to do in Second Life, am I right?

I tried to make a little joke out of it. This is pretty dorky, I warned him.

Again, yes, he said.

So I found Virtual Amsterdam on a map, and I zapped myself into it. This part is always nervewracking because when you go on any cross-world trip with a partner, you have to zap yourself away, and your companion is left standing there until he receives the telegram inviting him to zap to where you are. You worry, in those moments or minutes that he’s left standing there, he will abandon you.

Now I am trying to remember how I ever coerced Nikolaus into joining Second Life. I mean, it just isn’t the kind of thing he’d do—he’s a pretty cool guy. I know I helped him with his avatar. I do remember that. I watched him work on it.

He picked out a plaid shirt that looked exactly like those shirts in his closet I hate. I remember finding a decent pair of Converse Chucks and dark denim jeans that hung right. I knew the perfect pair of eyeglasses. I found a skin shaded with a faint beard. The wig was nearly a match.

I handed him a pair of sideburns.

After a long silence, as I watched him belabor his appearance, I asked him a strange question.

The longer you fix your avatar, do you find yourself becoming more and more attracted to it?

Yes. He said yes.

That made me feel better about being a pervert.

And the skin I bought for my avatar? It’s Japanese. Expensive. It’s very good, it’s almost photorealistic.

You’d never know it was Japanese if her clothes were on. When my avatar’s clothes are on, she looks a lot like me—mid-to-late-20s and white, and female. Maybe she is too feminine. Maybe the avatar’s eyes are oddly big and round behind the glasses’ lenses, but not too big, not too round.

I was ready for sex, so I removed my avatar’s clothing prims. It might have been a little like a striptease, except that the avatar’s shoes, blouse, skirt, hosiery, everything, poofed out of existence, one at a time.

Not too exciting; instead, comical. Maybe the tempo of my avatar’s getting-naked was all wrong.

She was down to her bra and panties, and her glasses. I hesitated.

I removed her glasses. My rhythm faltered. I didn’t want to go any further.

I wasn’t sure what she looked like. You know, underneath.

The bra disappeared. My avatar’s nipples were small and bright pink, like a child’s. Her breasts were small, too, and set high on her torso, though I recalled making them kind of big. Fascinated, I vanished the underwear. The avatar’s body was hairless, with a short, pink slit between her legs.

Oh, my God! I looked awesome!

Nikolaus was working to get undressed, too. He paused, reluctant to remove his shorts.

Then there was a shock of dark pubic hair. Otherwise he was as smooth and inchoate as a Ken doll.

“Oh, wow,” I typed to my boyfriend. Then, the obvious: “You don’t have a penis.”

In Second Life, to convey penetrative sex, the male is supposed to buy a dildo and pin it to his groin. I’m sure this part of the mating ritual—the part where the man’s boxer-briefs vanish, and now he is attaching an erect penis as if it were a clip-on tie and typing Ready when you are!—is a real scream.

We, however, were too naïve to even think of researching the science of sex. Without that essential dildo, the effect is nothing else than two mannequins falling onto each other, very exactly the way us 12-year olds used to make our fashion dolls hump.

I don’t want to describe sex in Second Life, but I guess I have to.

Where any coupled activity is possible, poseballs will likely hover. Here, a blue ball is floating in midair—for the boys!—and a pink one nearby for the girls, because almost everything in Second Life is heterosexual. And if the two motions are intended to operate together, the pink and blue balls will be fused together like a nutsack. Together they indicate, for instance, a park bench built for snuggling, a dance floor suggesting junior-high slow dances, or a bed probably meant for sex.

So in a rented room in Amsterdam, or in any sex room, there will be some jumble of user-made poseballs scattered all around.

First, the users must turn off their animation scripts, or else the sex won’t work. The idea is to use the animation already loaded into the poseball.

Next, situate the male avatar on the blue ball. Right-click the ball and, from the pie-shaped context menu, select the wedge instructing the avatar to “sit” on it.

Situate the female avatar on the pink ball by the same processes.

Now, with both avatars on their respective balls, they will automagically get down to business.

Of course, you can’t be sure of any poseball’s genuine function until your avatar is actually straddling it, pantomiming the moves its creator has designed. This can transform virtual sex into a shuddersome adventure of discovery.

“Oh, jeez!” I typed. My avatar was somehow on all fours, accepting sex in a way that made me uncomfortable. I right-clicked on the pink ball to make her stand up.

My boyfriend was left there, pumping his invisible penis into thin air, until he elected to stand up from his poseball, too.

“Let’s try another,” I suggested.

And now we were giddily visiting every poseball, attempting sexual positions my real-life boyfriend and I would never have dared to endeavor, all these strange looped motions some faraway inventor had configured for us. We were flushed from the innuendo.

“I’m a huge fan of your work,” I typed.

It was a jest between us. I used to whisper it doe-eyed way back when we kept the lights on, always right in the middle of things to creep Nikolaus out. “I’m a huge fan of your work, rock star,” or “I’m a huge fan of your work, professor.” I’d always conclude my endorsement with a disturbingly approving leer: You’ll never guess who I’m pretending you are right now.

III.

Second Life isn’t Sex Life, no; it isn’t all orgies and sex workers. I have kept myself occupied with plenty of other activities, thanks.

I have lost innumerable scavenger hunts.

I have camped at a simulated bonfire, listening to actual 1950s radio serials.

I have jammed myself into the bleachers of a crowded auditorium to watch celebrity game designer Raph Koster speak live from Georgia Tech.

I have dawdled in a Lovecraftian seaside village, have danced at a Prohibition-era-themed bar, have gone scuba diving in an ocean modeled after a pirate’s cove.

I have meticulously created a rollerskating airship pilot character for a steampunk MMO.

Certainly I have hoverboarded through a skate park.

I have worn a powdered wig to visit the Palace of Versailles. I have disguised myself in an Ultraman costume expressly to annoy patrons of the virtual Gion district. I have holstered guns beneath my bustle and canvassed the Old West.

I have complimented another avatar’s dress (“Thank you,” she replied, “it’s an Ivalde”).

Not only have I visited every house of horrors, I have toured that one haunted house specially designed to promote the 2007 Spanish horror movie REC. It’s provisional in glitchy ways, but it deliberately appropriates those shifting, tilting camera angles a scary Japanese video game would use.

I’ve even ridden a Ferris wheel with a teenaged boy. The carriage was so enormous, we were able to sit at opposite ends. If it had been a real carriage on a real Ferris wheel, we would have really slipped out, really splattered onto the planks of a real boardwalk.

Sitting on any virtual barstool anywhere, my toes cannot touch the floor. My hands clip the sides of pinball machines, my arms too short, evidently, to reach the flipper-buttons. And in most haunted houses, where I’d expect narrow tunnels and low ceilings and claustrophobic unease, the architecture is, instead, cavernous. Hallways yawn, almost as wide as they are long. Lofted ceilings vanish, stretching high above Second Life’s draw distance. Shopping malls are the same way. So are many homes. Doorways gape. Every window is a picture window. It’s easy to topple out from under balcony railings. Sofas seat eight. Lampposts illuminate the cosmos. Streets are eight lanes wide. Even the Chryslers are—to borrow a song lyric—as big as whales.

All this extra space for movement can be unnerving, perhaps scary. Awesome bitmapped expanses divide every home, tree, and davenport, so that I have to teleport, fly, or sprint to get anywhere in good time.

Maybe part of the trouble is, steering an avatar is more cumbersome than it looks. But here is the rest of the problem: my avatar is, in true-to-life measurements, 5’4”, or 1.63 meters. This is a white lie, of course, but it’s a real-world lie that my state-issued driver’s license will substantiate. In my virtual life, I like to uphold certain aesthetic principles about shortness and fatness, and these stalwart ethics are enough to get me excommunicated from many Second Life nightclubs.

I feel like a Lilliputian intruder because I am a Lilliputian intruder. I am a tiny troll. The average Second Life avatar’s height hovers somewhere between seven and eight feet.

I zipped my blue hooded sweatshirt and sat down. I opened my laptop computer.

“Oh, no. No.” That was Nikolaus from across the living room. “No. You aren’t.”

“Huh?” I looked at him. The login window filled my laptop’s screen.

Nikolaus was on my couch, craning his whole body over the back of it, looking at me. He was wearing my headset. He’d been online talking to friends, but now his microphone was muted.

“You’re doing it. You’re doing Second Life.”

How did he even know that?

Oh. The sweatshirt.

“What about it,” I said to him. “I have friends here. You go right ahead onto Halo, you visit your friends there.”

Nikolaus looked mad. I could understand it, in a way. Hadn’t I moved back into my apartment in San Francisco? Hadn’t everything turned out fine? Why did I continue to visit Second Life? Couldn’t I ring a friend instead?

He repositioned himself and again faced the TV, but he was stewing.

I rolled my eyes and logged into Lloyd.

Lloyd is probably the only region in Second Life where its residents—girls, mostly—dress like Vice Magazine’s Do’s and Don’ts. They buy and sell bruises, barf stains, crude hand gestures, short-shorts, and hamburgers.

I watched myself render. When you first reenter the Grid, you are a walking, talking fog of particles, fundamentally indeterminate and waiting to be realized. The landscape, too, starts out murkily, competing with itself to whet its pixels into anything remarkable. Slowly, all things jag into focus, one at a time.

“You guys! My boyfriend’s playing Halo!” my cloud typed to no one at all.

“Oh, no,” all the women in Lloyd replied.

Across the living room, Nikolaus grunted.

The worst part of it was, he knew the truth. The truth filled all the spaces between us.

That summer, I had been diagnosed with agoraphobia.

Finally, finally-finally diagnosed with onerous, paralyzing go away don’t look at me! Stop looking at me! Can’t go out, doesn’t phone, won’t write I’m too ashamed! Two hours’ pacing before making it to the front door, always lost, everyone can tell something is wrong with me, hiding on the toilet in a public stall, microwavable mail-order diet food, have another drink, honey, I’m drowning, I’m dead, no future, I’m finished. And he knew it all along! I had metastasized into an unremitting social cripple, and Nikolaus knew it.

He knew why I was zipped up in my blue hooded sweatshirt, hiding in Second Life. He knew, he knew.

Nikolaus was my last safe person. If he vanished, I vanished, too.

He was tired.

In the middle of our sixth year of dating, I left him.

IV.

An hour after midnight, nine nights before Christmas, we will hear my father hit the floor in his bedroom—some shambling, a clanging, then a muffled thud. He is somehow back on his feet before we can grab him.

“There are two things missing from this bed,” my father will whisper to me.

“Your dog and your wife,” I suggest.

“No, two small objects. Are missing.”

I guide my father to the bed’s edge. He gropes around for my hand, clutches me by the wrist: “I lost them in this bed. I can’t find them.” His eyes are wide and wet.

I peel the sheets back. I pretend to search. I make my hand flat; I pat the mattress.

“What have you lost?” I ask him.

“There was a… small… box,” he exhales, “metal. It opens.”

“Like a pill box?”

He shakes his head no.

“Describe the box for me.”

He holds his hands out in front of him, looking at his palms. “It was… longer than it was wide.” He frames a rectangle with his fingers, inventing it in the air between us. The missing object is the size of a penknife.

For my father, this is not unusual behavior. In the middle of the night, and for hours at a time, he will talk to me from inside his dream. He is transmitting his words from another dimension, a place that is grafted right on top of our one-story house.

“And when you opened the box, what was inside?” I ask him.

He is still phrasing the missing object with his hands, as if he wants to grab onto it. He frowns. “I… can’t remember.”

“Okay. And you lost this box. What happened next?”

“I woke up,” he tells me. “I’d just had it in my hands. I was using it. So I looked for it, here, in the sheets, like this. And then I got out of bed”—he stands up to reenact this—“to turn on the light to look for it. And then I was walking backward, like I was pedaling backward.” He staggers backward, demonstrating. “And I hit the wall.” As he does this, he really hits the wall.

“You lost your balance.”

He looks ashamed.

“Why didn’t you call?” I ask him. “Why didn’t you want me to help you look for your little box?”

“I am not making it up,” he says. “I knew you’d think I was making it up.”

“I know you believe you’ve lost something,” I nod.

He nods, too.

“But you also know you can look for it in your bed all night, and you will never find it.”

He nods again.

“So you are panicking,” I remind him, “even when you secretly know what you’re looking for isn’t real.”

“Panicking,” he repeats.

“Get into bed,” I tell him. He gets into bed.

“Legs straight?” I ask him. He pulls his legs into bed with him. He waits.

I pull the sheet up to his collarbone. I pull the fleece blanket to his navel.

Now he is shaking the sheets off. He kicks his legs. “This isn’t my bed!” he says.

“Why isn’t it your bed?” I look around. And I find it: there is only one pillow under his head, instead of two.

I plump a second pillow behind his head.

“There!” I tell him. “Is it starting to feel like your bed again?”

He works his head into the pillow. He nods.

“Are you scared?”

He nods.

“You don’t know what it’s like,” he whispers.

“Try to describe it.”

“I wake up in the night. The room looks strange. The TV is…”

We both look at the television set, hunkered low in the corner of his bedroom.

“It feels like it’s in the wrong place?” I ask him.

He nods.

“You wake up at night, and the TV feels like it’s in the wrong place. The bed doesn’t feel like your bed.”

He nods.

“And you can feel that something is missing. Why don’t you call for me? Maybe I can help.”

“I don’t want to,” he says. He smiles thinly. “You’ll think I’m nuts.”

“No, I won’t,” I tell him. “Actually, all of this sounds extremely—not normal, okay? But you aren’t so alone. What you’re describing is a feeling of uncanniness. In German, unheimlich, the not-at-home. In English, uncanny. So you wake up and you’re not-at-home. Something feels wrong. Everything feels like a dream. That isn’t so strange.”

I am trembling.

“In fact, it sounds a little like agoraphobia. I was reading about spatial theory yesterday. Um. Some neurobiologists believe that the real problem is vestibular. Or, okay, that’s basically the inner ear, which controls your balance. ‘Spatial estrangement,’ that’s what they call the weird feeling you get, if you can’t negotiate your surroundings the way you’re supposed to. It makes everything and everyone look strange. And that’s why you panic.

“See? So you aren’t alone. I feel anxious a lot, too. If you’re nuts, I’m nuts.”

My father wiggles the sheets off his arms. He hugs me.

This happened about an hour ago.

Agoraphobia—literally, “flight from the marketplace,” the incapacitating dread that afflicts shut-ins—is usually categorized as a subset of social anxiety disorder. Even so, researchers have long labored to pinpoint its origin.

At the turn of last century, sociologist Georg Simmel speculated that agoraphobia was a socio-geographical malaise unique to his era, a days-between-stations dysphoria caused by the static of modern urban space. People, Simmel decided, were not yet equipped to live in cities.

Contemporary neurologists’ spatial theory supports Simmel’s assessment. Spatial theory goes like this: people have more than five senses. We can sense pain, for instance, and temperature. We can also sense the passage of time, and we can sense space. We can feel where our arms and legs are, relative to the body (proprioception), and we also rely on an innate sense of balance (equilibrioception) no matter whether we are walking or standing still.

But if somebody has a bad sense of equilibrium hardwired into his brain, he will depend on audio and visual cues more than other people do. He must lean on these other senses to get his bearings, like a blind man at a crosswalk.

Too little audiovisual data—a cornfield, shuddering silently, with no landmarks on the horizon—and he automatically becomes lost. He is trapped in a dream-world with no exits.

Too much data—a crowded party, a shopping mall the day after Thanksgiving, a city—and he becomes overwhelmed with information. There is too much noise.

Of course I am oversimplifying. When I tell you “sense of direction,” I mean what French neuroscientist Alain Berthoz terms egocentric memory which, he writes, is the “vestibular memory of self-motion.” To use Berthoz’s own example, this means intuitively remembering what it feels like to make one full turn in the dark—a movement-memory stored in the inner ear to call up later and translate, by complicated synaptic algorithms, into a pirouette. Negotiating space using landmarks is, conversely, allocentric memory. Most people, in navigating from A to B, are able to combine those cognitive skills.

Anyone will experience discomfort when he can’t make sense of his surroundings, much less when he can’t understand how he himself fits into the big picture. But when that discomfort escalates into fight-or-flight physiology, it’s called a panic attack. And when a person with true vestibular dysfunction begins to associate cornfields and shopping malls with panic attacks, she is agoraphobic. An agoraphobic panics because she cannot estimate where she is in space and time.

Yes, “she”: agoraphobia is diagnosed between two and four times more frequently in women than in men.

In a watershed 2007 study led by doctoral candidate Jing Feng, researchers at the University of Toronto discovered, first, that women do not have the same spatial attention that men have—women were “not quite as good at rapidly switching attention among different objects,” Feng explains—and second, that the sex disparity in spatial skill disappears after women play a video game for just 10 hours. (Men, too, Feng’s team realized, benefited from game play, and in either case, the benefits seemed to stick.)

If it is true that agoraphobia is the body’s response to perceiving space badly, and if it is also true, as Feng’s team suspects, that a video game can rewire brains to perceive space better, then couldn’t virtual spaces be used to treat agoraphobia?

Immersion is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy used to treat anxiety. With anxiety, the amygdala is in the wrong gear, too easily stimulated, responding to any perceived threat—actual or imagined—by impregnating the body with adrenaline. Behavioral therapy is a resoldering of the brain’s circuits, building new synaptic connections through repetition, teaching the body and mind to respond to disturbing stimuli in more constructive ways than freak-outs and puking.

At its simplest, Virtual Reality Therapy, or VRT, might try to cure phobias by systematically desensitizing patients to facsimiles of frightening circumstances. In 1993, researchers at Clark Atlanta University’s VR lab studied subjects with agoraphobia, acrophobia (fear of heights), aerophobia (fear of flying), and glossophobia (fear of public speaking) by repeatedly plunging them into the virtual unknown. The 30 agoraphobics, along with other test subjects, markedly improved with VRT; at least two aerophobics were cured totally.

Dr. Max M. North and his colleagues determined, too, that the haptic simulations, no matter how blocky and low-tech, could capably frighten: “Remarkably, subject reactions consistent with phobic stimuli were experienced,” North writes, “in spite of the fact that the environments were visually extremely less detailed than a real scene” and had “simpler auditory and tactile clues.”

But North isn’t interested in immersion therapy. That isn’t quite why VRT works. Virtual simulations are effectual, North believes, not because they reproduce immersive, real-world situations, but precisely because they cannot.

Your sense of presence, North writes, is constant. Here’s what he means: if your embodiment of space were a pie chart, you would always be this much here and that much there, so that the slices of pie ought to add up to 100%. This is why, for a glossophobic standing at a podium, picturing the audience in its underwear can apparently work: he is 30% focused on delivering his speech, 65% pretending he is somewhere people are almost naked, and paying only 5% of his attention to pausing for laughs.

But establishing a virtual sense of presence requires a huge spatial and emotional leap—a calculated dissociation from real life. “Subjects have to give up the sense of presence in … the physical environment,” North writes, “to achieve a stronger sense of presence in the … virtual world.”

As the test subjects learned to externalize themselves, Dr. North discovered, their concentration—for an agoraphobic, “spatial attention”—improved. Patients were creating memories of movement inside of the simulation, the kinds of vestibular memories they never would have been able to form in real life.

To clarify, an example: what if I were to drive down Broadway, knowing I am supposed to turn my car left onto Thorndale? I have turned left onto Thorndale before, because I have lived in Chicago before, but every time I try, that left turn becomes a life-or-death contest. So I barrel toward my intended street, dangerously, staring at grocery stores and pedestrians walking their dogs. Too busy to recognize my surroundings, too unable to prioritize the city’s visual information, I inevitably pass Thorndale. I only realize I’ve missed it when I am several blocks farther down Broadway, probably at some horrible, impassable intersection where I cannot cross the lanes. I overcorrect, making a series of right turns and trying to keep track of where I am, and now I am lost in a network of residential one-ways. In my panic, I pull my car over, smarting from humiliation and wondering why I ever left the safety of my apartment. This happens every time.

But if I use a GPS? With its easy, three-dimensional model of the city streets, Thorndale’s approach is made obvious. I check the 3D map. I compare the real city against it. As I near my left turn, I am compulsively looking at the GPS’s tiny screen, checking my reality against its version of it. Turning left onto Thorndale is a success.

Then, naturally, someone breaks into my parked car and steals my GPS—and because my burglar has a sense of humor, he leaves my metal compass in the front passenger seat, right on top of my glove compartment’s Rand McNally—but at least I have learned to visualize this one left turn. And now, every time I drive down Broadway, I picture Thorndale lighting up ahead of me, as if the real world were more like the world my GPS invented.

In the same way, VRT does not teach agoraphobics to negotiate physical space at all. It’s the opposite. Virtual Reality Therapy can teach us only to maneuver through virtual reality spaces, and then graft the memory of these spaces onto everyday, noisy existence.

Perhaps, in the end, agoraphobics cannot develop true vestibular memory. We will never have a sense of direction. To function, perhaps, we must remain 60% in a noiseless dream-vacuum, and only 40% in the din with the rest of you.

V.

What time is it there? is how any virtual conversation apprehensively begins. We concluded that we were in the same time zone.

Why are you still awake? will be the next thing we ask each other.

The woman explained to me, in a smaller chat window, that she was in her mid-50s. She explained that her mother had finally gone to bed.

Her mother—!

I explained that I was 27, and that my mother had finally gone to bed, too.

Then she told me her mother was ill. I told her my mother was also ill. Then she told me how old her mother was. I told her our mothers were exactly the same age.

Then I told her, also, about my father.

She types the word: caregiver.

Never in these few short years have I met another caregiver.

We typed, back and forth, about resentment and guilt, about how angry we were, how isolated we had become. We were added unto each other; we were struck down by our paired grief. We typed excitedly.

Then, when we agreed that in our separate lives it was time to go, she sent me a telegram inviting me to be her friend. And I accepted, so that when we are both online a notification will pop up and tell us so. And when I log on, she will always ask me how I am doing. She is the only person in the whole world who knows to ask me how I am doing.

But I do not log on. My mother finally agrees to hire some people, so I leave Texas, I return to my small new life in Chicago, and so I do not visit my virtual life. Months pass.

This year, she emails me. She hasn’t seen me in awhile. She’ll start us off, she says, by telling me her real name: Jenny.

My reply is painfully short, short enough to murder our friendship, except that from Chicago I suddenly cannot think of anything else to tell her: “My name is Jenny, too.”

I am 28 years old. I am adopted.

My parents adopted me when I was 11, a few months before they bought our first computer.

Today, my adoptive dad is in the stage of Alzheimer’s that comes right before eating paperclips and right after pooping on the carpet. He is not ‘all there’—he has a few toes in our world, and the other six live in a limbo that is neurologically unknowable.

My mom, who is not so elderly as my dad, has two implanted robot knees, which were a good idea until she developed a type of staphylococcal infection called MRSA. The infection spread. In mid-October, her kidneys failed. The infection moved to her eyes, blinding her. Then it traveled to her spine. In December, her doctor told her—as if he were sharing some snip of mean gossip—that she will not live.

I am in Texas, overseeing my parents’ care, juggling lists, walking their dog.

If you ask my adoptive dad to please do something, or to please stop doing something, he will shout that he is 90 years old. He might try to hit you with his feeble 90-year-old fists. He wakes in the night, hourly, and he can’t fall asleep again until he is tucked into bed. You will stay up all night. You will catch snatches of sleep during the day. He is upset that you are asleep when you ought to be awake, so he wakes you. He follows you through the house. And now he is pressing on the circuit of three questions he has asked every few minutes for the last 145 minutes—what are you doing, what are those buttons you are touching, when is my wife coming home, what are you doing, what are those buttons—and you are trying to type this magazine article, and at last through gnashed teeth you tell him you will put all the answers on a sheet of paper for him to keep. You find a pen. He is furious. He grabs you by the arm and tells you to get out of his house. You sit down in a chair and scream.

If you want to touch my mother, you are supposed to wear latex gloves.

Here, from a room where all my past is framed or shelved or stacked in drawers, I spend a lot of time wondering how I am going to get myself home. Home is a rented apartment in Chicago, while I have been living at my miniature childhood desk for three long months.

I don’t mean to say that the stigma about Second Life is true, but maybe it is true for me.

Maybe I am so consumed with living other people’s lives out for them, I have to transmit myself to an imaginary world to feel as if I could live my own.

Maybe I am not all here anymore.

It is 2:00 a.m.—midnight, Second Life time—and I am going to church.

This is the right time to go to church, I think. Two in the morning is when the ache of God’s absence becomes shrill.

Time operates differently in Second Life. Linden Lab itself is in San Francisco, so, reasonably, Linden time is synchronized with Pacific standard. But here, in this other world, the sun rises and sets every four hours.

In wintertime it is the landowners’ duty, as caretakers, to spackle the landscape with snow, to hang berried wreaths and fill the air with soaring sparrows, to pin icicles individually to every awning, to imbue the island with its authentically artificial immanence. So the ground is snowy, dappled with carotene-yellow sunspots. The sky is blue. The birds trill gaily.

I am dismayed by all this daylight. I consult a drop-down menu and, with a few clicks of the mouse, the moon rises, the firmament filling itself with flat stars. Ah! Now it is nighttime for me, for me and nobody else.

Lately the church’s island has become perplexing: here is a gazebo I don’t remember; there, I guess as a heavy-handed religious metaphor, a stray sheep. I am completely turned around. I open a world map. I point my cursor toward the grouping of little green dots. There! That must be the congregation, assembling itself for morning service.

When you pass under the grey stone arch of Second Life’s Anglican Cathedral, you are supposed to arrive at a long buffet table. Here you can make donations to the church, if you are into the tithing thing, or grab a program that outlines that morning’s service.

You click on the program, trying to pick it up. A window pops up, asking if you would like to add the sheet of paper to your inventory. You hesitate. You wonder why it must be so difficult to pick things up and put them down again.

Right-click on a pew and, from the resulting context menu, choose to sit on it.

Scour your inventory for today’s service. In it, scriptures and canticles are reproduced from the Church of England’s official website. Now you have to rapidly move back and forth between the two windows, copying and pasting text with cunning acuity, as if church itself were a twitchy hack-and-slash.

But maybe you don’t copy or paste. That’s fine, too. Relax.

You follow along with the call-and-response’s script:

The pastor says into her microphone, “O God, make speed to save us.”

“O God, make haste to help us,” you whisper at your computer to no one, lit dimly in the dark.

She lilts, “Give peace in our time, O Lord.”

“Because there is none other that fighteth for us,” you reply.

Perhaps you don’t hear anything, because your microphone is muted and everyone else’s microphone is muted, but in that silence you know there are other people whispering along with you, keeping pace.

After the service, as you are struggling to rise from the pew, maybe other people will try to talk to you. You don’t have to answer. That isn’t impolite; accidents happen.

If you are spooked you can just zap yourself away, as if you never heard them calling out to you.

As a teenager I became puzzled by improvised prayer, and the use of electronic drum machines in hymns, but especially at being greeted—at being hugged and lovingly interrogated—every Southern Baptist Sunday. I wanted liturgy. I wanted litany. I wanted ritual, and limestone archways, and pipe organs.

Online, I have met church members from Australia, New Zealand, England, the Midwestern United States, and Germany. I have seen sermons pronounced without so much as a hiccup, in spite of furries—that is, users dressed as cats and foxes and bears—gathering at Compline. Not even a leather-clad woman and her partner, collared and leashed and crawling down the aisle on all fours, could stall a morning service.

Something is safe, and canny, about having all the words already drafted. Everything is musically timed, so that nothing can deter your rhythmic certainty. You can keep your place on the page. You are nowhere, and everybody is right there with you.

At 3:00 a.m., when we finish, I am joyful and melancholy, staring into my future. I think this is presumably the correct reaction to church.

In the autumn of 2009, my parents suddenly converted to Roman Catholicism. They wanted to be buried together, and I guess there is such thing as Catholic dirt.

“Should I be Catholic, too?” I asked my mother. By then I had been thinking awhile about turning Episcopalian.

“Oh, sweetheart,” she said, putting her fingers to her forehead as if to unpinch her eyebrow, “no.”

VI.

I was sitting in a friend’s armchair, where a single strong drink had made me brave. So for the first time, I told anybody, I told her, that I’d tried Second Life sex. And another thing: I’d attended Second Life church. Telling it was, in the distance of my own breath, a relief.

Oh, my God! she’d said, and she actually recoiled. Gross!

Well, I said, flustered, they were separate events. It isn’t as if I had sex in church.

Still! she said. That’s so bizarre, that you would do both those things.

Why was I so disappointed? It was credible criticism.

People do both things in real life, too, I said carefully. I don’t know how to describe it. The church is real. Sex wasn’t.

Okay, she said. But why would you even do those things?

Why would I even. I wondered, too.

There are all these stupid, whiny, scientific words, and religious words, to describe being lost and scared. But I could not even begin my description. I felt around, but everywhere we ought to have been connected, there was a blank space.

How could I explain Second Life to somebody who had never visited it?

Could I describe agoraphobia to someone who isn’t wired that way? How to explain caregiving—that crazed isolation that only women in their 50s know about? Could I explain never arriving on time, never finding stray objects that needed to be found? Could I make myself known?

Why am I telling you all this?

She waited—she did not abandon me—but I didn’t have anything else. I shrugged. There was no good explanation. I really was some kind of demented.

I kept wondering.

I wondered all the way to my car. I used my phone to map a route from her apartment to my apartment.

I wondered as I drove. I wondered while I parked. I wondered in my bed.

Why would a woman stay and stay, trying to learn the impenetrable language of some foreign country, jogging only forward and backward in time and space, with no knowable destination within the draw distance?

If I could recast our conversation in my favor—if I could make my words more important, and my thoughts incisive, if I could apologize properly for being bad at most things, like timeliness and explaining myself, and love, if I could make anybody listen—I would set my drink down. I would lean forward, my elbows touching my knees, and I would strike every consonant like the clap of a bell, plummy and pedantic as if I believed I were worth listening to.

Have you never, I would say, studied the human condition?

No, I wouldn’t say that. I would never. Let me try again.

My answer would be smaller, and timorous, but more direct:

The same reason anybody does anything—to feel as if she might not be turning, turning, turning, on this uneven axis in the dark.

![]()

originally published in Kill Screen Magazine, Issue 3: the Intimacy issue