The quotes on the box are marvelous:

“I first saw this program in the same week that evidence was discovered of life on Mars. This is more exciting.”

That was Douglas Adams.

“Call it a game if you like, but this is the most impressive example of artificial life I have seen.”

That was Richard Dawkins.

It was the summer of 1997; the software was Creatures, for Windows 95, Windows 3.1, and Macintosh. I was nearly 15 years old, but not quite.

Creatures wasn’t so much a game as it was an artificial life simulation. To begin, you choose one of six eggs, depositing it into an incubator. This is how you birth your first creature, a “Norn,” a sort of baby bear-cat-mogwai with wide, expressive eyes and a spindly, dwarfed body.

You can only parent the Norn in four ways. You can tickle him, spank him, bring objects to him and speak to him. It is most important that you speak to him; this is how the Norn learns language and, eventually, how to parse right from wrong.

The game has bad guys — of course any game must fabricate conflict by having bad guys – called Grendels. They will kill or infect your Norns. You must teach your Norns to be afraid of Grendels. In this way, the game can learn to play itself.

When your male Norn, for instance, reaches sexual maturity, you might think about consulting your limited repository of eggs. Maybe you could birth a female Norn so that you can cross-breed creatures until, much further down the genetic line, you have a stable of creatures like nothing the software’s programmers intended.

![]()

When I was 14 years old I had a subscription to Wired magazine. The magazine had talked about this game Creatures in a very breathless way.

In one apocryphal story, a Norn had become ill, had died, and another Norn – the two had always been inseparable – refused to abandon the body. Eventually both creatures were dead. The devoted Norn had starved to death by waiting.

“You can’t program that!” one of the software designers had told the magazine excitedly. (This isn’t an exact quote, but it’s close.)

I read this story in Wired, and I was thrilled.

![]()

Oh, sure, I had toyed with life simulations before. After all, I’d kept an egg-shaped knockoff Tamagotchi chained to my backpack; had tortured the pet as a sort of experiment; had cried helplessly when it left me.

![]()

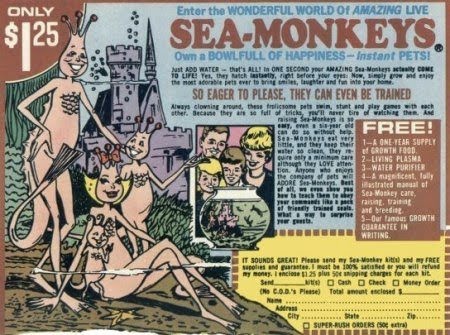

As a child I was obsessed with the Transcience Corporation – I owned a pair of X-Ray Spex and I was not too depressed when I discovered how the illusion worked – but I was especially fascinated by the Amazing Live Sea-Monkeys.

As a child I was obsessed with the Transcience Corporation – I owned a pair of X-Ray Spex and I was not too depressed when I discovered how the illusion worked – but I was especially fascinated by the Amazing Live Sea-Monkeys.

In modern days, instead of four packets, there are only three, which are numbered procedurally: #1, “Water Purifier”; #2, “Instant Life Eggs”; #3, “Growth Food.”

There is some sort of chemical interaction when Packet #1 meets Packet #2, and this is how Sea-Monkeys are born. (“Newly hatched Sea-Monkeys are no larger than the ‘period’ at the end of this sentence,” the instructions say.)

In the meantime, the instruction booklet itself is a dramatic work of science fiction.

Q: “How long will my ‘Instant Life’ packet last before I use it?”

A: “How long has never been established, although Sea-Monkey eggs have hatched after a decade! Sea-Monkeys exist in suspended animation through a process called ‘cryptobiosis’. Once the eggs are poured into treated water, they ‘magically’ come to life!!”

“Suspended animation.” I had never heard the term before, but I loved the idea.

Maybe we are all in love with the idea. What if we could all hang suspended in a perfect instant, totally untouched by death?

What if we could wait as long as we like? What if we could simply wait for that perfect instant to bring something, or somebody, back to life?

![]()

I sent my cash allowance to the Transcience Corporation, ordered other packets.

If you empty a packet of powder called “Super Food,” your Sea-Monkeys might evolve to incredible proportions – up to an entire half-inch. If you empty a packet called “Cupid’s Arrow,” Sea-Monkeys may get busy and multiply which, to the fledgling Mendelian geneticist, makes a certain economic sense. If you empty a packet called “Red Magic,” the Sea-Monkeys might blush with rosy health.

And then again, if they become pale and sick, maybe a packet of “Sea-Medic” will fix them.

But it wouldn’t always fix them; much more often, the entire tank of Sea-Monkeys would die. Sea-Monkeys were always a little better at dying than living.

Still, there were always more eggs in the basin, an entire crust of unborn creatures, an entire reef of eggs. So you could drain the tank and add more water, and there they were! All these little punctuation points, flagellating happily again.

![]()

You probably already know this, but Sea-Monkeys are just brine shrimp.

![]()

Creatures did not resemble any game I’d ever played. Death, it seemed, was so permanent. You couldn’t undo death. Once a Norn was ill or hurt, it was difficult to stop the process.

Creatures did not resemble any game I’d ever played. Death, it seemed, was so permanent. You couldn’t undo death. Once a Norn was ill or hurt, it was difficult to stop the process.

And there was something else, too – every Norn had a limited lifespan.

Worse, every Norn was living life at a speed that was too too much faster than my own life. There was no way to do enough to save each of them.

Every Norn was hurtling toward death. This, to my 14-year-old self, was terrible.

I certainly did not embark on Creatures to learn any timeless truths about death. I had already been touched by death, repeatedly, even at that green age.

I have often joked about how much I would like to own an African Grey: I would like to be outlived.

![]()

Creatures remained popular long after it was out of print. Players modified the code so that Norns might reproduce with Grendels. They added entirely new objects to the environments. Other players traded their Norns online. The game evolved just as the real world evolves.

![]()

You could never copy or clone a Norn, but you could transfer a Norn as a Save File. Once you’d done this, though, there was no way to continue him. You had to start all over again with another egg.

And I did this! I did this to my Norns!

Anytime I had a perfect moment – a snapshot of a perfect life – I would save the Norn onto a floppy disk. I would transfer the Norn, leave him on a floppy disk, and suppose that this was something like “suspended animation.”

I decided, in this way, my Norns might live forever: I would wait for each Norn’s perfect moment, and then I would hang the creature onto a floppy. Someday, I decided, I would ‘reactivate’ each of these Norns.

I could have found a workaround – I could have used Windows to duplicate all these Save Files – but unfortunately I was not so computer-literate when I was 14.

Anyway. Having done all this, I would manifest a new Norn altogether. I would hatch a new egg and start over. If I ran out of eggs, I reinstalled the game. I did this again and again.

This is not how the game is meant to be played.

![]()

One day, when I was visiting my adoptive mother in Texas, I sat at the old computer and shuffled through old floppy disks. I was looking for things I had written as a teenager; I had saved all those stories to disks too.

And this was how I found all of these labeled disks, one after another: a name and a date. A name, a date. A name, a date.

I realized these were all Norns.

I thought about what I had done to these creatures. I thought about how I had wanted to save them.

I was not looking at save dates. I was looking at epitaphs. I was looking at headstones. This was not suspended animation at all. I had made coffins.

I had been paralyzed by my own fear of mortality, and so, one at a time, I’d paralyzed my Norns.

I had not saved them from their own too-short lives. It was exactly the opposite: I was so frightened of watching them die, I had murdered them instead.

![]()

Someone once asked me, in one of those ridiculous anonymous “ask me anything” forms, whether “the liminality” “had” me.

“GET OUT OF MY HEAD,” I replied.

![]()

I am terrified of being a mother.

When I was six years old, I announced my intention to adopt (I myself was not adopted until I was 11). Even at age six I was so concerned about my own genetic code, about passing such things on. I was worried about some sort of genetic fate.

I recently discussed this with a close childhood friend who herself is a new mother:

“Oh, sure,” she said, “it would be incredible if children could come out already six years old. You could just help them with their issues instead of inventing new ones.”

Then she admitted that, at night, she panics. She panics about all the myriad ways she might hurt her new child.

So there was a certain biological humor for me – and I think I have mentioned this before, but surely I have not mentioned it here – when I discovered I probably cannot have children. Probably I cannot. Probably I am made up of the wrong software: I am an infertile soil for certain life simulations.

And anyway – and I don’t mean to be grim – a healthy 30-year-old woman is only 20% likely to become pregnant, if she is even trying. After that, the odds of inventing life plummet.

Oh, there are certain things you can do. There is no such thing as real doom, after all. You could take control of your destiny, if you wanted. You could try drugs like Metformin and Spironolactone. You could save all your money and eventually try something like IVF. I don’t know. I don’t know.

I’ll be honest, though. I don’t want it enough.

![]()

One time a teenaged boy came into my work, and after we talked for awhile about paintings, he asked me if I thought he could live with me.

“Um,” I said.

“What,” he said.

I felt awful. I had moved around a lot, myself, before I’d found the people who would eventually adopt me.

“You would not want to live with me,” I told him. “I don’t have the money anyway, but also, I would mother you. You would not want to be mothered by me.”

He blinked.

“And,” I said sighing, “I think I should probably meet your parents.”

He returned a few days later with his father. We shook hands.

![]()

I’m lucky.

I look at these floppy disks and I realize how biologically lucky I am.

Probably I would be the worst mother. I would smother, not mother. I would invariably prefer that a child be trapped in this single perfect stage, saved to a floppy disk, rather than allowing him to move on, to somehow worsen. I know just enough about motherhood, and I know this about myself.

But there is a nightmare of a thought here: I am full of latent life, but it is all suspended animation, which is really only another word for dead.

There is something endlessly melancholy when a bit of software can do what you physically, emotionally, genetically cannot.

![]()

In Creatures, there is always this moment where any single Norn finally learns to call you by name. The feeling that comes with it… I don’t know what it is like to be a mother, but sometimes I can guess.

![]()

originally published at Unwinnable; reprinted with permission by Kotaku