The two scariest things my mother ever said to me were ‘I thought you would have a family by now’ and ‘that little dog will be yours someday.’

Most days, if I’m working, I ignore my mother’s dog. If she’s really feeling neglected, she will stretch to her full height, which isn’t much, and push against me, her forepaws in the small of my back.

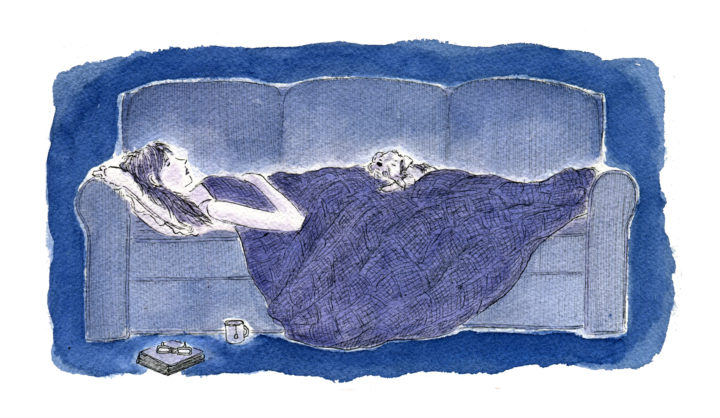

At night, when I sleep on the couch — it’s always on a couch — she will sleep too, a warm gray curl fitted in the crook behind my knees. At night, if I’m working — I’m always working — she will pretend to be asleep but never close her eyes.

Sometimes I will turn to my mother’s dog and whisper, “Hey, do you wanna…” just to see her sit up and tremble. She is waiting to hear how the sentence ends.

“Don’t tease Tootsie!” my mother will chastise, loud in my mind’s ear.

“All right, all right,” I will grumble at no one. “Toots, do you wanna go for a walk.”

![]()

My mother’s dog is a miniature schnauzer, a stocky little thing made of perfect right angles and, I think, nerves. When her fur is overgrown she looks less like a dog, more like a stuffed bear. She is so cute when she trots or gallops, when she howls or sighs. She is always sighing. Mostly I avoid looking at her directly. Looking at her feels like a heart attack, my chest gets so tight.

![]()

“I know this is going to sound crazy,” I told the veterinarian, “but she’s on the couch too much. Usually she shadows me around the house, but now she just sits there. And — how do I make this not sound crazy — her butt isn’t as perky as it used to be.”

The veterinarian smiled.

“I’m very impressed!” he said to me. “The problem is her spine.”

He put his fingers against my mother’s dog’s back, near her haunches.

“It’s actually this vertebra right here.”

Then he said, “You will be an excellent dog owner. I know the type.”

He winked.

In the waiting room, the receptionist put her hand on my arm.

“Do you want your name on the paperwork,” she asked. She was pointing her clipboard toward me. I looked down at it, at my parents’ names.

“Um, not yet, that’s all right,” I said. Then I clapped my hands over my mouth at the very memory of both of them, and gagged. I tried to not vomit in front of her.

![]()

Once, as a child, I made the mistake of asking why I wasn’t allowed to have a dog.

“Poisoned!” my adoptive father shouted in lieu of an answer. “They were poisoned! Rat poison! The neighbor! The neighbor did it!” He scowled and beat his right fist against his chest, as if to ward off some epic dole.

I got a parakeet instead.

![]()

I didn’t want a dog. Now I can’t picture not having a dog. Now, when the dog gallivants across the lawn in pursuit of a butterfly or squirrel, my chest becomes so small and tight with love-panic. Of course I am trying to imagine losing her, trying to prepare myself for what that day will feel like — or worse, what all the days after that would feel like.

In quiet moments I turn and look at my mother’s dog and hold my breath, watching for the almost-imperceptible rise and fall.

“Toots,” I might whisper to her, “do you wanna…?” because I am making sure she still comes alive.

There isn’t a longer, more terrible grief than a dog owner’s anticipatory grief. “A dog,” writes John Homans, “can’t figure out that it’s being measured for its grave.”

![]()

The two scariest things my mother ever said to me were “I thought you would have a family by now” and “that little dog will be yours someday.”

“Please don’t talk like that,” I snapped.

![]()

I used to drive alone between Chicago and my parents’ house, which is twenty-something hours away. During college break I’d sneak into their house in the middle of the night and sit down at the kitchen table with a book or a sandwich.

My mother would invariably wake up first, would appear in the kitchen in her Snoopy t-shirt and boxer shorts, thrilled. It wouldn’t be long, would it, before my adoptive father lumbered in. “Well!” he would bellow from the doorway. And then he wouldn’t hug me; instead he would cup my head in his great, heavy hands, would handle my face roughly before patting me, hard, on the shoulder.

Then it would be all three of us, sitting around the kitchen table with our cups of coffee, interrupting one another.

Once, when my mother was in the hospital, I sneaked into the house, dropped my luggage in the den. My mother’s dog quickly found me out. She threw herself at my feet, a yelping whimpering whorl.

“Well,” my father said from the doorway, “who is it?”

“Hi!” I said. “Sorry to wake you.”

He frowned at me. “Who is it?” he repeated to the dog.

“Oh,” I said, my chest balling into two rolled fists, becoming smaller than any other feeling I’ve ever had. “No, it’s me, Jenny. Your daughter Jenny.”

“Jenny!” he said. “Well! I wondered why the dog was going nuts.” He staggered toward me, took my face in his great, cracked hands, and pressed my head, hard, to his sternum.

This was probably the last time my father ever called me by name.

![]()

I hated her as a puppy. She barked at literally everything. Her shrieks would turn to growls when my father or I went to hug my mother.

“You aren’t even listening!” I shouted.

“Hmm?” my mother asked, her head jerking toward me. “Oh. I hear you. You were talking about your English professor.”

“God!” I shouted, rising from the couch and crossing the living room in one easy motion. “Enjoy your replacement daughter!”

“Jenny,” my mother said, but I was already flouncing down the hallway toward my childhood bedroom, which never had a locking door. I slammed the door anyway, flung myself onto the bed.

I waited for my bedroom door to open, but no one came.

“God,” I whispered into a pillow. I shook, furious.

My mother had pleaded with her husband to let her have a dog, and after years of refusing, he finally told her yes. He had driven my mother to the farm, had chosen the whimpering thing himself, had held that squirming little potato in his great, gnarled hands.

I rolled onto my back, resolved to stew to in my childhood bedroom all night. I put a pillow over my face.

“Jenny, love Tootsie,” my mother would order, pointing at that wriggling clutch of teeth and toenails and fur.

I’d eye the dog, unconvinced.

“She’ll be yours someday,” my mother would say then. Her voice would become low and serious, a warning.

It wouldn’t be long, would it. I wondered how long a dog lives. I gritted my teeth, then sobbed into the pillow. My father had made it clear: my parents both expected to die within the dog’s lifetime.

That animal was an egg-timer.

![]()

I will be 31 soon. I write about videogames for a living, same as I did when I was 24.

Everything else, though, is different. For one thing, there’s this dog.

She’s nine.

Sometimes we are walking together — me, shuffling and grumpy, hating the outdoors, her, nuzzling each individual strand of grass, it would seem — when someone will stop me to say, “Hey! Cute dog!”

I immediately reply, “Thanks! She was my mom’s.”

“Is she friendly?” the person may ask, stooping to get sniffed.

“Of course she is friendly,” I answer impatiently.

My mother’s dog is waiting by my feet right now, pestering me with her plaintive looks.

Sometimes I stop typing and look down at her, like this. And she hears the pause and she looks up at me with those wide, wet horse-eyes, just like this.

And I have to smirk at her, I have to, because here we are, just the two of us, only ever just the two of us, what a pair. Probably we are the only pair in the world that has ever really made any sense.

![]()

originally published at The Bygone Bureau