The original Game Boy is always called the original Game Boy.

In the videogames industry, where everything is in flux and obsolescence is planned, this naming convention—”original Game Boy”—is anomalous. For instance: We often refer to the first PlayStation, retroactively, as the “PS1.” Even original-formula Coca-Cola is called “Coke Classic,” while old-school Mountain Dew is branded as “Throwback.” Sometimes we will call an Xbox an “original”; here, we are only distinguishing from the 360, which is what we really mean by “Xbox.”

We call it the “original Game Boy” because we must. That little device was so fruitful, so ambitious—and so studied, so imitated by its own creators—that we have to stop ourselves mid-sentence to clarify exactly which Game Boy we mean. We don’t mean the first one, or even the best one: We mean the original one, the innovative one, the font from which all handheld inspiration would eventually spring.

Which is kind of funny. The device—it was first released in North America 30 years ago this week—was, in the beginning, unwieldy, the size of a paperback novel split in half. Its plastic surface had an inauspiciously ashen complexion. In-game screenshots never ethically disclosed that the LCD was, not grayscale, but in fact the precise tinge and timbre of seasickness.

The handheld was all clumsy corners and 90-degree angles, too, except for the deliberate curve of its bottom-right edge, or that jaunty pair of candy-red buttons. Ten years after the Sony Walkman, here at last was a device that felt equally hefty and capable, indestructible and permanent. (The optional battery pack, attached at the player’s waist with a clip, was sized and weighted exactly like a potato.)

The original Game Boy’s cartridges weren’t cartridges, either; they were “Game Paks.” Every Pak, box and corresponding game manual was embellished with a golden Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, a guarantee not that the Game Pak would work, but that every other game cartridge would fail.

Listed below are, without argument, unequivocally the ten greatest Game Paks to ever grace the original Game Boy’s soupy-green display.

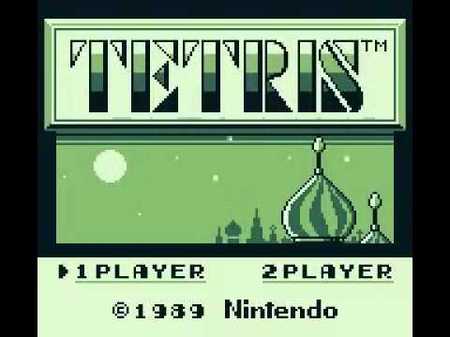

Tetris

1989

When the Game Boy launched, Tetris was already five years old and readily available, in honest-to-God color, on computer and home console.

It didn’t matter. Tetris, the cartridge prepackaged with every Game Boy, is the variation generations will remember. It is the game grown adults stole from their own children after 9:00 PM. Players complained of nightmares about falling bricks.

Make no mistake, it is possible to win Tetris. Upon the completion of “Game B” mode, Tchaikovsky’s “Trepak” plays blank”>as the citizens of a Russian diorama dance along. Then the %28spacecraft%29″ target=”_blank”>Buran—a space shuttle that launched only once, in 1988—blasts off into the heavens. In this revision of history, Russia has won the space race. It’s wistful.

More important, though, Game Boy’s Tetris introduced a side-by-side two-player mode; competitive play required a “Game Link,” or “wire,” which physically tethered the player to her opponent. All bets, forevermore, were off.

Super Mario Land 2: Six Golden Coins

1992

To be fair, Six Golden Coins, the sequel to 1989’s Super Mario Land, owes much of its dynamism to the SNES game Super Mario World.

Mario, no longer a blunt instrument, is now a leaping, whirling, floating, interesting hero—at least, as 2D platforming heroes go—flying through the skies on whimsical bunny ears. (The way Mario oozes his way through tree sap is a tactile lesson in “gamefeel” fit for any fledgling designer.)

The endgame pits Mario against a brand new boss villain—some nobody named “Wario”—who, just as soon as he is defeated, reveals himself as a simpering pity-partier.

The third in the Super Mario Land series is 1994’s Wario Land, which deliciously perverts play mechanics from Six Golden Coins even as it investigates new ones. And though Wario Land trumps its predecessor in many ways, Six Golden Coins is perhaps the eminently more replayable of the two, thanks to its non-linearity, its meatiness and its very difficulty.

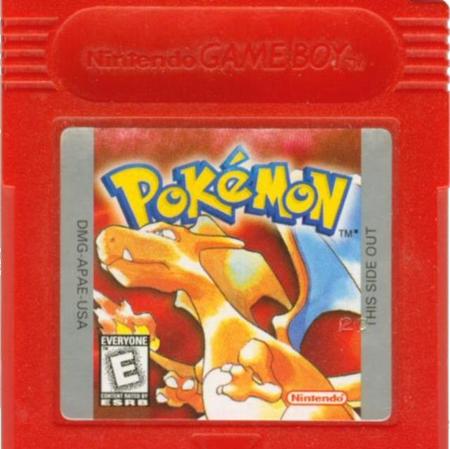

Pokémon

1996

By the time Pokémon tramped onto players’ radars, the trusty Game Boy was already seven years old. The handheld’s technological hoariness did not seem to deter the multitudes of modern American schoolchildren suddenly and unanimously gripped by the game’s refreshing, agnostic depiction of good versus evil.

An anime cartoon arrived the following year; the Pokémon Trading Card Game came the year after that, in 1998. By 1999, it was the parents who had whipped themselves into a fervor over the “Pokémon craze”, certain that the games were unnecessarily violent, that the cartoons themselves induced seizures in otherwise healthy children. A vocal minority convinced itself that Pokémon was demonic.

Probably most interesting—and to some moral watchdog groups, alarming—was the way children clustered on playgrounds, “battling”, as it were, using little Game Boys strung together. In reality it was as harmless as tin cans connected by thread.

“It hasn’t even peaked yet!” toy expert Ira Gallen warned a disbelieving Brian Williams. With distance, we can smile in relief: How right Mr. Gallen was.

NBA Jam

1994

It is weird, yes, to stake an SNES port—here, now, like this—on a top-ten list of best-ever Game Boy games. But, where ports like Mortal Kombat and Battletoads were indeed noticeably hamstrung—whether by technical or aesthetic abstractions—NBA Jam excels.

NBA Jam is played two-on-two and, in its Game Boy incarnation, all four basketball players handily fit onscreen. Granted, these four are silhouettes of their former selves—they look like basketball-playing brine shrimp, basically—but these sylphs move every bit as fluidly as their big-screen counterparts. The roster is complete, and the music isn’t too bad, either.

Considering, NBA Jam is the unlikeliest of all possible outcomes: a game that doesn’t look quite like the original, but sure plays like it.

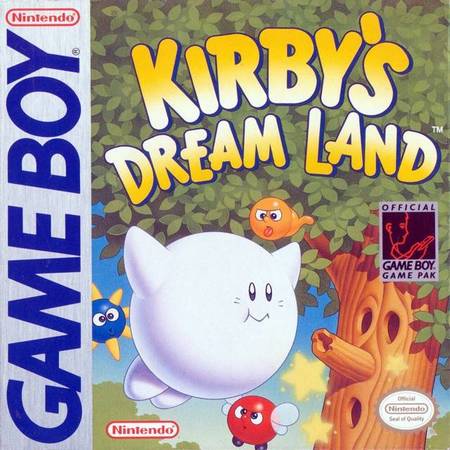

Kirby’s Dream Land

1992

Kirby is a rarity. He is, by all appearances, too sugary-sweet to be heroic: He is the exact color of Hubba Bubba, with the wispy weightlessness of spun cotton candy. He’s also unique in that he debuted on the humble Game Boy—Kirby was no port.

Rather, Kirby was the eponymous hero of an all-new adventure, Kirby’s Dream Land, a fever-dream about a cream puff with a killer case of the munchies, augmented by amphetamine-laced chip music. As an offensive measure, Kirby spits out stars: His rotund body contains, presumably, entire galaxies, maybe universes.

One short year later, Kirby would play the lead marble in Kirby’s Pinball Land which, while only glancingly related to the original title, is the best pinball game available on Game Boy, no question.

Kid Dracula

1993

Kid Dracula, or Akumaj? Special: Boku Dracula-kun, is a lighthearted game for the Japanese Famicom, improvising on the popular Castlevania franchise (which, even in 1990, numbered a whopping six entries).

A sanitized (read: less incomprehensibly racist) version of the game appeared on U.S. shores for Game Boy in 1993. In that game, too, Gothic settings are populated with stylized “chibi” villains.

But this game isn’t your cute baby brother; it has teeth. Soon after establishing itself as a send-up, Kid Dracula abruptly turns on the player, disclosing itself as no parody but, instead, an actual legitimate gosh-darn Castlevania game.

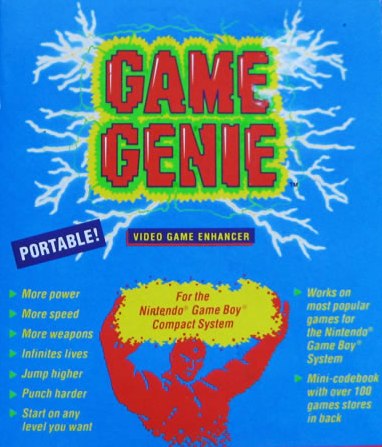

Game Genie

1992

You tentatively insert the massive gadget into the slot you know only Game Paks ought go. The Game Boy starts normally, but then the opening strains of Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue” (the Phantom of the Opera’s favorite ditty for pipe organ, natch) ominously sound. Oh, man. Oh, man. This product is not licensed by Nintendo—the opening screen even says so!

For people of a certain age, nothing was more transgressive than Galoob’s Game Genie, an unlicensed peripheral that effectively doubled the size of the Game Boy. The game cartridge itself, in turn, had to be inserted into the Game Genie’s slot—in reverse, the Nintendo fan equivalent of hanging a cross upside-down—whereupon a cheat code, nine characters or more, could be entered by meticulous hand.

An impossibly thick spellbook of cheat codes was stored in the Game Genie’s hinged compartment for easy reference. But newer games weren’t listed in that arcane, thumb-sized tome, so the player had to experiment. Entering cheats blind could be downright terrifying: Floors would fall out from under the player; villains and obstacles would flash in and out of existence; music might glitch in horrible ways. To a ten-year-old player it was like summoning the Devil himself, and it was so, so wrong, and it was glorious.

The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening

1993

Link’s Awakening is an RPG experience so whole, so timelessly replete, many players remember it—inaccurately—as a Game Boy Color title.

And while 1998’s Link’s Awakening DX does boast full color, shoving the original cart into a Color or Advance slot uncovers an approximately-correct color palette. That’s because Link’s Awakening is so good, its palette was built right into the Game Boy Color, so that if you happen to plug the cartridge into a slightly newer machine, the machine bows down and recognizes. (The Game Boy Color also has inbuilt “special palettes” for Kirby’s Dream Land, Super Mario Land 2, Metroid II and Tetris, all of which have or will appear on this list.)

Link’s Awakening is the fourth installment in the Zelda series—it, a prequel, directly followed 1991’s A Link to the Past—all at once improving on earlier entries yet while adapting itself to the tiniest screens. (Its most faithful kin is probably 2005’s Minish Cap, another wonderful title.)

Metroid II: Return of Samus

1991

Metroid II: Return of Samus is, for many, the most detestable of the Metroid series: The Samus sprite, for one, is ungainly, too big for her small screen. The map is constantly dammed, not by locked doorways but by lava; the game’s potentially circular route can prove frustrating.

Seldom will a direct sequel arrive on handheld or, when one does, it’s usually no matter of importance. But Metroid II’s Samus sprite—her movements, her “look”—went on to become the definitive depiction of the 2D character.

And as individual entries in the Game Boy catalogue go, Metroid II is the best and most frightening example of disorientation, exploration and the horror of discovery. Metroid II is no platformer; it’s survival horror, less Sonic, more Dead Space. Meanwhile, the game’s sparse, organic soundtrack only escalates the player’s sense of alienation and dread.

In short, Metroid II is to Ridley Scott’s softer-spoken Alien as Super Metroid is to James Cameron’s sequel.

Final Fantasy Legend II

1990

Trickily, Final Fantasy Legend and its sequels are no Final Fantasy games at all—they’re actually the first of the SaGa franchise—but the Final Fantasy Legend trilogy earns its braggadocio nonetheless.

The best of the three is Final Fantasy Legend II, that rare whippersnapper that can, without real contradiction, be invoked as a fast-paced, turn-based, challenging scamp of a fluff RPG.

Sound familiar? It should: The game is, screen by screen, menu by menu and sometimes letter-for-letter, 1996’s Pokémon. (But better.)

![]()

If Wikipedia is to be believed, there are at least 706 other Game Boy cartridges floating around.

But these—the games listed above—are the best ones. These are the triumphs. Some games further the form; others skate by, merely defining entire franchises. A scant few manage to do neither, all while reproducing the gamefeel of their big-screen parents.

In any case—and this is not the exception but the rule—the original Game Boy consistently defied its own technical limitations, often to surprise and delight.

And while more powerful, probably more fascinating handhelds coexisted within the Game Boy’s 14-year lifetime, no other portable device, save perhaps the Sony Walkman, can ever aspire to match Nintendo’s once-and-future empire.

![]() originally published at Paste

originally published at Paste