I tented my fingers, bending them into a writerly stretch. Then I poised my hands over my new laptop’s keyboard, a musician ready to compose on her instrument. I froze, waiting for inspiration to strike me down.

It wasn’t right, I wasn’t ready. Something was missing. I’d already installed Scrivener, for writing; Notepad++, for blogging and code; LibreOffice, for editing other people. And WordMenu, for coming up with words like “aposiopetic.”

Now that I had assembled my workspace, I was too bored to work. Instead, I began inching my cursor toward the Steam icon in the bottom-right corner of the laptop’s screen. I’m stressing myself out, I reasoned. I need to vegetate. But everything in my game library looked too heavy. Even the thought of Osmos exhausted me.

Then it hit me. “Snood!” I shouted at my laptop. “I haven’t installed Snood!”

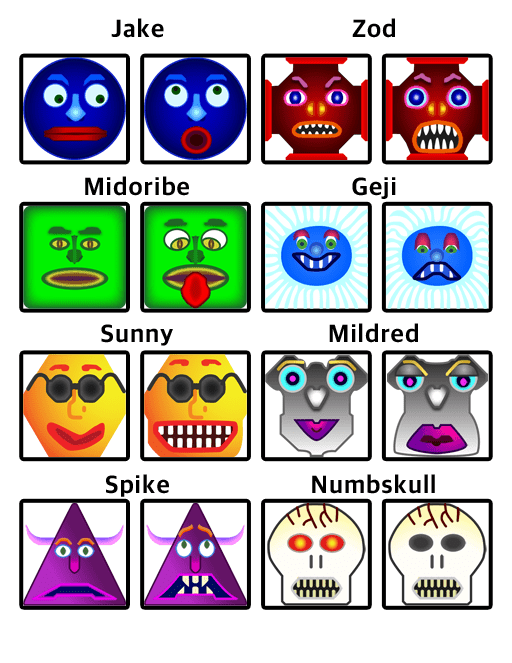

At the outset of any Snood session, more than half the playfield is filled, without gaps, with a wall of characters straight out of a Martian bowl of Lucky Charms. These are the eponymous snoods.

There is the game’s most memorable snood, Round Blue Head. Then there’s Purple Triangle with Horns, Yellow Hexagon in Ray-Bans, Angry Red Robot, Boring Green Square, Pale Blue Hairball, and my personal favorite, Lady Horseface.

Their facial expressions change, but you usually only catch those shifts out the corner of your eye. They idle in this really disconcerting way, too: The hipster hexagon may suddenly grimace, while the green square might stick out his tongue. It isn’t your imagination: Yes, they’re insulting you.

Snood first insulted me almost 14 whole years ago in the “computer lab”—really, just a pair of computers with a printer strung between them—that was then located in its own room on the first floor of Chapin Humanities Residential College, where I lived as a student. In the gray hours before dawn I must have been sitting there stupidly, hunched over a portable coffee from Burger King. Probably I was trying to wring out some fascinating typewritten insight for my next class. Possibly I was coaching the printer into printing that fascinating typewritten insight (triple-spaced, margins set to a billion).

In those days dormitories were collaborative black markets. Dozens of us were running the same copy of Half Life (mine); we unanimously upgraded from Windows 98 to XP on the same borrowed registry key. By the end of our first month as students, we all had the same Aimee Mann album.

No one’s printer ever worked, either. Mornings in Chapin were a scramble, teenagers half-dressed, floppy disks (!) in hand, running from room to room. The few sad sacks who used Zip drives had nowhere to turn.

“Go to the computer lab,” we’d lazily remind one another, “downstairs.”

I had started taking my own advice. It wasn’t just that the lab’s printer was slightly more reliable than mine: I’d discovered I actually preferred working on a public computer. It was slow, and the Internet connection was slower. The lab itself was always quiet, always empty—but other people had been there! You could see their documents right there on the desktop! Any evidence of human life was reassuring at 4 AM on a Wednesday.

On the computer desktop, crowded in among the students’ saved files, I remember there was a single strange, stray icon. It was bizarre, even horrible, a round blue marble of a head with severe red lips. It was awful. I wondered who among us was responsible for putting that icon there.

Of course I double-clicked it. That launched a window with a list of high scores. I recognized most of the names as classmates.

Oh, it was on.

Snood itself is a lot like Puzzle Bobble. A turret presides over the bottom quadrant of the screen, and you, the player, move this turret with your mouse in an arc from left to right. Pick a trajectory, click the mouse button, and another snood ejaculates onto the playing field, making a satisfying “thoonk” not unlike the pneumatic “thoonk” from an arcade’s air ball cannon. Match three snoods of the same color and type, and they vanish. Knock other snoods away with them—a “two birds with one stone” type of play—and they drop from the screen with a little triumphant fanfare.

Clearing the screen of snoods means a game is won. But when an errant snood trespasses the bottom demarcation of the playfield, it’s game over.

A lost game is especially unsettling. All the faces abruptly turn to skulls, presumably because you have failed to “rescue” or “free” the snoods. A short funereal dirge plays, too: Nice going, savior, they’re all dead.

***

At its height—right around the time I was a student myself—Snood was “the rage on campuses around the world and elsewhere.” (Fittingly, the game itself was designed by a university professor.)

Snood was released in 1996 as shareware. And shared it was, on some aging co-op of a computer located in one of Northwestern University’s oldest buildings. It quickly became known among our ranks as a brilliant procrastination tool.

In my dorm mate Mary Hawkins’s case, playing Snood once made her late to a class that was held “in a building so close I could see it out the windows of Chapin’s computer lab.” (If you must know, I can tell you from memory that Mary was looking at the Music Hall.)

As a young editor, Jeremy Parish—he’s now the senior editor at USgamer—played the game on his “miserable little PowerBook.” “Snood was my go-to,” he said, “when I was sitting in the university newspaper office waiting for other people to turn in their assignments.”

Matt Marrone, an editor at ESPN, is a few years older than I am. “I played it to death at grad school while listening to local right-wing talk radio,” he told me. (He adds that “it was a very different time.”)

Meanwhile, Kotaku video editor Chris Person is a few years younger than I am, and Snood was installed on his high school’s computers. “Snood was the only game they let on our Catholic school computer labs,” he said. “In retrospect, I’m not sure if they put it there or if the students did.”

From 2000 to 2002, Michael Crassweller actually managed a computer lab at Penn State. “Snood was the bane of my existence,” he told me. “Students kept finding ways to install it.”

It really was only installed in labs, too, wasn’t it? I don’t think it ever once occurred to me to install Snood on my personal machine.

Wrong, my former dorm mate Angela DelBrocco corrected me. “Pretty sure all of us would crowd into your room—Tony’s room? Kyle’s?—and watch demonstrations, until we thought it was a good idea to spend about 137 hours a week playing,” she said.

I don’t remember that at all. I asked Angela, Is this true?

“Yeah,” she told me, adding that, eventually, every student in the dorm had installed Snood. A fellow Northwestern grad, Sherri Berger, backs Angela’s account. “I can confirm that it was on every PC in Chapin,” she said.

Did you play a lot of Snood in college? I ask my best childhood friend this question at lunch today.

“Not really,” she said—and then she sighs—”but I remember you trying to get me to play it.”

Snood is turn-based, rather than time-based. There’s a running meter to the right of the playfield and, as you take each of your shots, the meter climbs ever nearer to its pinnacle (“DANGER!” the meter’s apex is helpfully labeled). Any time your meter fills, the playfield is ratcheted from the top so that the field becomes one “line” shorter, the wall of snoods apparently quickening its approach.

Most important, Snood does not actually reward you when you manage to match three faces; on the contrary, the DANGER meter continues to fill at its usual pace. In this way, “matching three”—the basic mechanic of an endless array of puzzle games to follow—is not the object of the game at all, since even matching three goes punished by the meter.

Instead, the goal is to take out several many snoods at once. This, it would seem, is the only way to quell the DANGER meter. Bringing that meter down low again buys you enough turns to ultimately clear the field and beat the game.

Snood, at its most masterly levels, becomes a strategic balance of resource management. If you have a purple triangle, you’re better served flinging it toward a pair of blue marbles, since—provided another blue marble is coming your way—you can handily dispose of those marbles and the purple triangle, thereby briefly satisfying the DANGER meter.

It’s funny that the game urges you to “save” the snoods, when actually you’re sacrificing them. You’re practically throwing them into a volcano.

Yet for as simple (and incredibly dramatic) as it sounds, describing the game is not easy. Kimra McPherson—a 2003 graduate of the Medill School of Journalism—sent me a magazine-style article she’d written, as a onetime class exercise, about her roommate playing Snood.

“When she matches three like-colored Snoods,” Kimra wrote, “all three disappear, zapping from the playing screen with a flash.”

Here, Kimra’s professor underlined the phrase when she matches three and, in red cursive, he wrote “I don’t follow.” (He has also inexplicably struck the word “zapping.”)

Kimra quoted her roommate’s explanation—”The more bricks I have at the top, the closer I am to dying”—to which the professor wondered, in marginalia, “Why? Less space?”

“Valiant,” the professor wrote on Kimra’s third page, “but I’m still not fully clear. Perhaps if I’d spent my youth playing more pinball, I’d understand.”

B+.

Still, it would be a mistake to assume that Snood only appealed to students and pinball-players.

One day, my Northwestern classmate Yana Bourkova-Morunov paused at a ground-floor office window and stared in, startled to see a professor playing Snood at his desk. Perhaps he was waiting for his visiting hours to end.

“I thought it was funny,” she told me, “and just stood there watching him.

“He kept looking up at the clock and right at 5 PM he turned off his computer and left it. It reminded me of the opening scene in About Schmidt.”

***

My work laptop is a stone-cold killer, its blade honed for productivity. Software like Fotografx and WinSCP—for editing photos and file directories, respectively—are spare and bells-free.

I have done my best to reproduce an environment not unlike the machine I, as a focused and driven college freshman, might have liked to use. Only four games are installed to my work laptop: Brogue, Tyrian, Civilization V (ahem) and Snood 4.

Because, while the work I produced as a teenager was not by any stretch the best, it was almost always finished on time. With that in mind, I have consciously elected, as a freelance writer, to go right ahead and embrace distraction.

Much has been made of the writerly propensity for procrastination. Psychology Today encourages blocked writers to “boost motivation” with a “reward and penalty system”: “After every hour of work, take five to ten minutes for a planned enjoyable activity. Then get back to the writing activity until you finish.”

“Procrastination,” muses book critic David L. Ulin, “is a necessary part of the puzzle, a way to deal with the discomfort of laying ourselves out on the page.”

A few hours after I’d purchased Snood Deluxe (which is the latest version of Snood for Windows), I found myself returning to the website to download an older, shareware version of Snood 4. As I did this, I experienced a chill of déjà vu: I’d done this before. I suddenly realized, with a start, I had already purchased Snood Deluxe on disc a few years ago, and had replaced that version of the game with Snood 4, too.

I can’t put my finger on why later versions of Snood don’t do it for me. I don’t think it’s just nostalgia at work here, though.

As with all games of a certain age, what I remember most about Snood is that I used to be a lot better at it. An adroit player—the player I used to be—might nimbly shoot a snood into a narrow spot that, frankly, makes no physical or scientific “collision” sense. Fitting your snoods into those crawl spaces is a knack instrumental in winning. The very best players have become veritable pool sharks, bouncing snoods off walls into pockets.

Snood is unlike most falling-brick games—titles like Lumines or Puyo Puyo or certain variations on Tetris—all games in which a playfield begins mostly empty and then endlessly fills. This game is more like Dr. Mario: It’s about chipping away at the garbage that already exists onscreen, while trying your best to not add to the preliminary burden.

It’s a fine game for a writer to keep running in the background on her work laptop. It also makes for a serviceable metaphor—supposing metaphors are your thing—about writing and writer’s block, for instance. All we ever do is chisel away until finally our screen is cleared.

![]()

originally published at Vice Motherboard