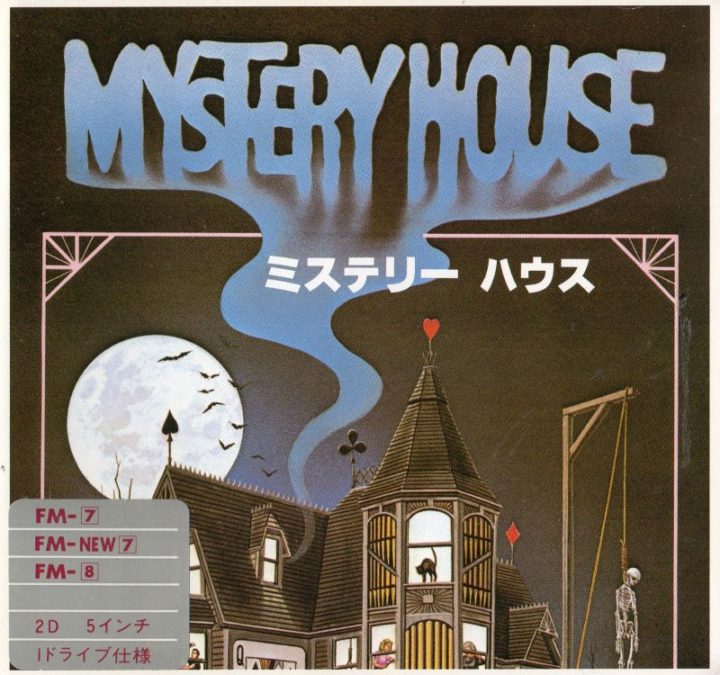

Mystery House (Apple II, 1980) was the very first release from Sierra Online. Husband-and-wife cofounders Ken and Roberta Williams mailed the game in Ziplock baggies. They eventually sold over 10,000 copies.

A word of warning, though: Mystery House isn’t any fun.

“By any standards it’s an incredibly abusive play experience,” game designer Erin Robinson explains. She goes on to add that “the graphics have zero sense of perspective, and background lines travel through solid objects.”

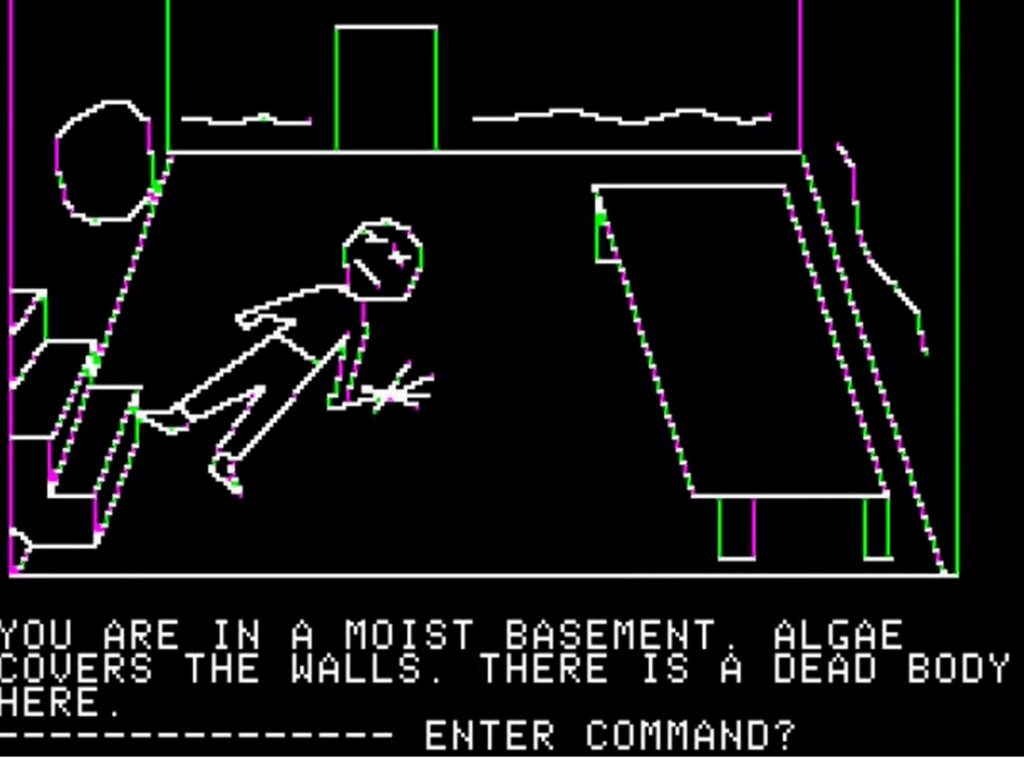

Crude green-on-black line drawings accompany sparse lines of blocky text. The houseguests aren’t particularly memorable, either. (Sam, for instance, is a brunet gravedigger. He’ll be among the first to go.)

Meanwhile, the game’s prose doesn’t exactly aspire to Shakespearean heights. “Because they only left themselves room at the bottom of the screen for about two lines of text,” game developer Jake Elliott says, “the textual room descriptions are necessarily terse, almost to the point of breaking down.”

Worst of all, playing this style of game requires interminable patience and resolve. Because surviving the mansion uses a rudimentary parser, players must type exactly the right thing to make any progress. The commands themselves—”north,” “look room”—have not yet evolved from the stilted, stodgy interactive fiction of the time.

BioShock‘s Ken Levine tells 1UP he’s never been a fan of the genre—it is too syntactically unforgiving, its narrative too linear. Robinson adds to the pile-on: “The designers gave you dozens of new ways to lose a video game, and only one incredibly obtuse way to win,” she says.

Even to hear Sierra cofounder Ken Williams describe it, Mystery House is unapologetically derivative. “I would love to claim originality,” he tells 1UP, “but much of Mystery House was borrowed from other places. The idea to do an adventure game came from the text adventure called just Adventure, and the plot was loosely influenced by a movie, The House on Haunted Hill.”

How can a game that is so torturous, so primitive, so derivative—and so ugly!—be voted by 1UP readers as one of the most important and influential games of all time?

Levine is quick to explain why: “I [do] admire the work they did,” he says, “uniting graphics and a form of storytelling.”

Oh, something interesting had happened, unquestionably. When the player typed “open door,” the still image onscreen would suddenly change, so now the door really was open! When the player investigated the interior of a cabinet, instead of only being told about a box of matches, she would also see the matchbox.

This changed everything.

Simply by mashing up pictures and words, Roberta and Ken Williams’s Mystery House had inadvertently invented an entirely new genre: the graphical adventure game.

In an email, game designer Al Lowe (Freddy Pharkas, the Leisure Suit Larry series) remembers seeing Mystery House for the first time. “I watched those white lines trace out Roberta Williams’s drawings at lightning-fast (well, for then!) speed, and the text appear below,” he writes. “It was amazing. Remember: no one had ever created an adventure game with anything but text!”

Lowe recalls playing through the Williams’s subsequent releases with enthusiasm. “I was forever hooked on Sierra games,” Lowe tells us. “I still remember vividly that day 30 years ago when Ken approached my humble little table at the final Applefest and yelled back at Roberta, ‘Hey, Berta—these games look just like yours!'” Lowe concludes, “It was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever had.”

Jane Jensen—she collaborated with Roberta Williams on King’s Quest 6 and more recently founded the studio Pinkerton Road—notes that, although Williams was known best for her fantasy games, “she did have a good ear for mystery and enjoyed writing mystery games.”

Indeed, and from the very get-go, Mystery House had established another genre altogether: the graphical mystery-horror.

The Colonel’s Bequest—which is the first in Roberta Williams’s much-too-short Laura Bow series—is a direct successor, a spiritual sequel to Mystery House. That game occurs in a mansion, too, and characters are again killed off one-by-one. This time, though, the game is more accessible for newcomers, the graphics have been updated, and aspects of the game are timed.

Jensen points to The Colonel’s Bequest as an invaluable model for her own work. “Laura Bow was always a favorite of mine, and one of the best classic mystery games,” she tells 1UP. “The first Laura Bow was an influence on Gabriel Knight 3, specifically the way it structured blocks of time where each suspect was doing something during that period of time, and you could miss it if the clock moved forward and you hadn’t seen it.”

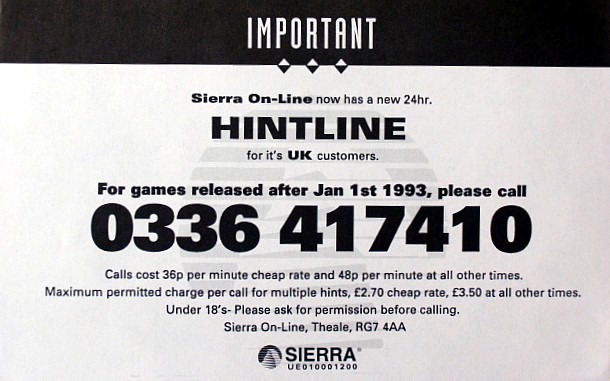

Mystery House‘s influence ripples in an unexpected direction, as well. Because the game was so difficult, it inspired history’s first “hint line”—which, unfortunately, was right in the Williams’s own kitchen.

“Yes, the original hint line was our home phone,” Ken Williams tells 1UP in an email. “That didn’t last long, once we realized that people outside the US were playing our games and we’d get calls in the middle of the night.

“Later, we experimented with lots of different ways to provide hints, including magic ink hintbooks and bulletin board systems,” Williams continues. In that regard, the subsequent phenomena of strategy guides and Internet walkthroughs—many of which are fan-scribed—owe deeply to the Williams’s very own kitchen telephone.

Best of all, Mystery House resulted in the founding of Sierra itself. While many female developers often find it difficult to break into the modern-day mainstream games industry, Jensen remembers Sierra as a boon to women: “I was lucky getting into Sierra Online,” she reminds 1UP, “because there were already a number of strong female designers there—Roberta Williams, Christy Marx, Lori Cole. So I never felt there were any stumbling blocks at all in my path.”

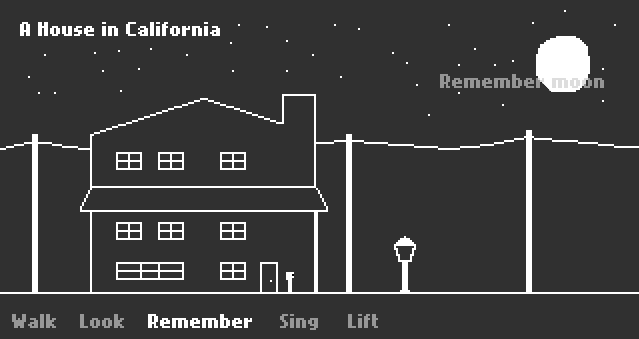

Mystery House‘s influence extends into the present, too. Jake Elliott—whose minimal adventure game A House in California was nominated for the Independent Games Festival’s coveted 2011 Nuovo Award—was inspired by Mystery House a full 30 years after its release.

“I was experimenting with this one-bit white-on-black pixel art and really feeling insecure about the idea of using images at all,” Elliott remembers, adding that he felt more comfortable writing. Then, he says, he discovered Mystery House. “It was this game about a bunch of people in a house, just like my game,” he tells 1UP, “except that this was a cruel game about people being cruel to each other. That was a very instructive point of departure for me.”

Erin Robinson, a designer working right now, adds, “Although the adventure genre is fraught with design problems, it hasn’t stopped me from making four of them.”

To be sure, Mystery House is plagued with problems of its own, but that certainly hasn’t kept fans from remaking the game over and over.

What makes Mystery House so important, so special? Robinson has a pretty good idea: “There aren’t many other cultural forms from 1980 that people are still talking about.”

![]()

originally published at 1UP.com