On Friday, Rhizome published a restoration of three CD-ROM games from the 1990s by Theresa Duncan, which you can play here. Duncan’s work has been largely and unjustly forgotten since the 1990s, and this restoration project was inspired, in no small part, by a 2012 article on Duncan’s work by Jenn Frank.

Here, Nora N. Khan interviews her about her life in gaming. —Ed.

Acclaimed writer and games critic Jenn Frank is widely known for her excruciatingly intimate memoir essays, in which she often probes her family history and girlhood nostalgia to illuminate why games have been vital for her personally and, by extension, for many others. Her work also explores how players engage with, and imagine themselves, in relation to systems, to the sets of rules established by a game world.

Frank uniquely renders games as profoundly human, explicit articulations of longing, curiosity, awe, fear, and love. Her work is very important to me, and to many other writers and game developers, and when she stepped away from games journalism for a time last year because of harassment, it was a real blow. Now she is publishing again, cautiously, and in an effort to better understand her importance, I spoke with Frank over email about her personal history, her lifelong relationship to games, and her part in shaping games criticism as a form.

Nora N. Khan: Let’s start from the beginning. Could you tell us a bit about where and how you grew up?

Jenn Frank: I primarily grew up in a small town in coastal Texas, which is a place very unlike what most people visualize when they think “Texas.” This part of Texas is mostly little run-down beach communities: houses on stilts, palm trees, antique stores, fresh shrimp. It’s humid; it looks and feels like Florida. Geographically, it’s nearer to Mexico than it is to Dallas. It’s also sort of remote, locked by land on all sides except the side that is the Gulf of Mexico.

And—I think this is important also to note—I moved here, no kidding, by myself when I was 7 years old, from Seattle, to live with my great-aunt and great-uncle, these much older relatives who eventually adopted me. Until then, I’d been bouncing around the Pacific Northwest to live with all these different people. By the time I was 7, I’d decided I should have myself sent to Texas, so my grandfather packed me up and put me on a plane. So I was still really young when I got here, but I experienced an extreme sort of culture shock anyway.

Meanwhile, my great-aunt and great-uncle, Midwesterners who’d never had children of their own, were really very conservative, even for Texas—not only because they were evangelical Christians, but also because of their age. So they held some very dated ideas about parenting. These people sent me to school each day in a party dress, patent leather mary-janes, and those little socks with lace eyelet at the ankles—every day until third grade. I looked like the main character from The Bad Seed! So my peers were right to be terrified of me. Elementary school was a very rough time.

NNK: So, you’re in this humid, remote, coastal town in Texas. And you were already playing games from a very young age. What is your earliest memory of playing a game? What did you find yourself playing in the 1990s?

JF: One thing that was very culturally shocking or jarring for me was moving to Texas and being told I couldn’t play video games any more. Now, to be fair to them, my elderly relatives didn’t count the Game Boy library of games as “video” games—their suspicion was explicitly of “TV” games—but still! No more TV games! I couldn’t believe it. Until I moved to Texas I’d lived and breathed video games!

Basically, they didn’t want me mirroring my father’s behavior at all, which I understood even then, but I also grasped that the household video game ban was misguided, albeit well-enough intentioned. My birth-dad, meanwhile, was this really funny, nerdy kid, who was super into Jim Henson and D&D and ’70s fantasy and probably Monty Python. He was also a loving but incredibly irresponsible father, which is to say, he struggled terribly with depression.

We had an Atari 2600, and he was really good at Mountain King —which is roundly remembered, in retrospect, as probably the hardest game for that system—and to this day the Atari 2600 is my favorite system, and Mountain King is still probably my favorite game for that system. Dad also played a lot of Berzerk, so I do, now, too. I guess those are the two games I probably revisit most, even though I’m not necessarily very good at either. And so a lot of my very earliest memories are of these 2600 games.

My dad came to visit me in Texas when I was 9, and we went to an arcade together and talked about Atari games and arcade games, and that’s a happy memory. He died the following year. I was 10 and he was 35: he was just a couple years older than I am now.

NNK: That’s a really lovely memory. What happened next?

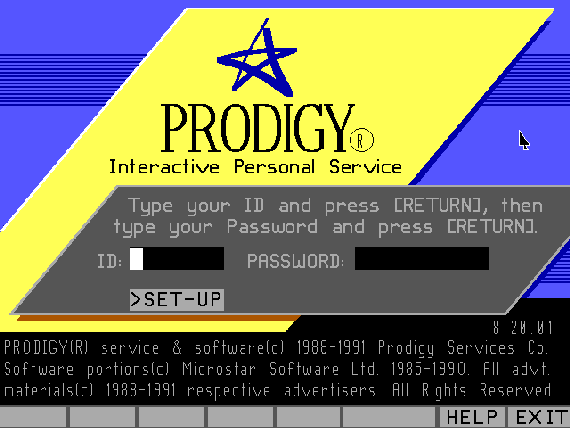

JF: My great-aunt and great-uncle adopted me proper the year after that, and that same year we got our first computer. It was a Packard Bell 486-33 that came preloaded with Prodigy, which is an AMAZING thing to give to a maladjusted 11-year-old girl living in one of the more remote parts of the United States.

My piano teacher gave up trying to teach me how to read music and started teaching me how to use DOS instead. It was wonderful! So of course, now I wanted to install software on the computer and, more specifically, I wanted to look for this one piece of “edutainment” (in actuality, a rudimentary, roguelike piece) I’d first played on the computer in a “gifted” class.

Well, there was no way my adoptive mom could argue with that. The child wants to keep learning at home! Amazing! So she set down a new edict: “Video” games were still off-limits, but “computer games” were fine, I guess, because they rang as somehow more “intellectual” to her.

By 1995 we were one of the first houses in town with dial-up internet—not Prodigy, not AOL, not Compuserve, but an actual ISP. By then I was telnetting to bulletin boards, running up a huge phone bill.

NNK: Were there games that were off-limits to you? And could you speak more to what games offered you emotionally and intellectually as a teenage girl?

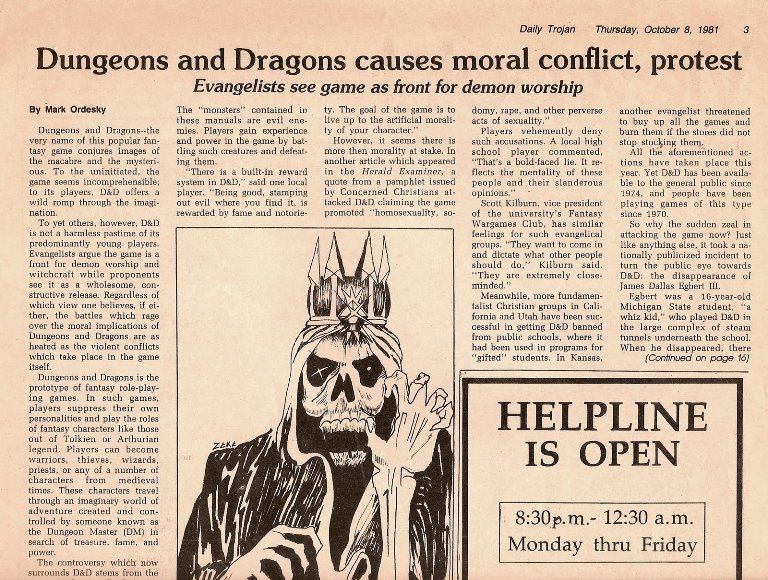

JF: One thing I was definitely NOT allowed to play were role-playing games—RPGs. I think the younger set might not remember the “Satanic Panic” of the 1970s, and it might surprise even the slightly older crowd to learn what a long tail that moral panic really had. For the uninitiated, though, it was the widespread fear that playing Dungeons & Dragons could spiritually “open you up” to demon possession–a fear that lasted well into the 1990s and even after that.

For the purposes of our own household, RPGs were defined as any games with “character creation” screens (the real fear surrounding RPGs being that kids were “becoming” or otherwise emulating their characters). My adoptive mother’s explanation was something like “God made you in His image and you should be happy playing as whatever character you were assigned at the start of the game.” In practice, this meant King’s Quest games were fine, while Quest for Glory games were not.

As SOON as we had internet, I started telnetting into MUDs. I played so much Shadow of Yserbius, too! I was pretty sure that, by my adoptive mom’s logic, Betrayal at Krondor would be okay, but it didn’t seem like the hours of explanation WHY it was okay would be worth the trouble. So these were the first things I ever kept hidden from her—I kept no other secrets from her, to a fault—and all this sneaking-around was really more for her sake than mine. To this day, I have only ever played the PC version of Final Fantasy VII.

By high school, I kept the computer games thing a half-secret from many of my teen-girl peers, but I was still rushing home every day to play whatever I was stuck on at that moment. MissionForce: CyberStorm, that was the really big one. (I also had a Bikini Kill album that I listened to at a *very low volume*, so as to not offend my parents, who preferred Karen Carpenter.) By then, I was getting zines in the mail, reading really strange books, listening to weird music you could only mail-order.

Even though I never got used to Texas, I had a really fantastic “inner life,” is what I’m saying. I also wasn’t allowed to watch R-rated movies, or play M-rated computer games, until I turned 17. While I regret having such a huge gap in my knowledge, I don’t resent it at all. So there are a lot of cultural touchstones and signposts I completely missed in the 1990s, with the benefit, a little counterintuitively, of being free to seek out other stuff I personally found interesting.

When I turned 18, my best childhood friend gave me an Atari 2600, and my adoptive mom was so mad! I took it with me to college. I kept the Atari hooked up to a VCR which, in turn, was hooked up to my computer monitor. My freshman-year roommate hated me, because I’d given everyone in our dormitory copies of Half-Life and Team Fortress.

NNK: You’ve talked a lot about games as a third, Nth, other space — a “place you go,” more than something one plays. What happens to the mind and heart in that space when we enter it?

JF: Playing Mountain King makes me feel 3 years old again, because there is such a sense of place and time attached to that game for me. So, when I “revisit” that game I’m also visiting my dad, because games are these weirdly liminal places that are “just how you remember them” when you return to them. They aren’t like street blocks, right, which gentrify or crumble or otherwise change in uncanny ways. You always feel such grief when you discover an important location from your childhood no longer exists *as it did*.

Games are *reliable*. They’re a reliable type of memory. They’re reassuring in an existential way: “Okay, I’ve been remembering this correctly.” I’ve talked before about “sense of presence” and being in two places at once and “where-were-you-when.” So I can readily describe to you what was going on the last time I played Castle of Illusion, or how I was feeling the last time I really sat down and played Galaxian. I can remember where I was sitting better than I can details about the games themselves.

When my adoptive mother was in the ICU for the last time, I abandoned my Chicago apartment and everything in it and drove to Texas. And then when she passed away, I sat alone in my childhood home—in the last several years it was constantly full of nurses, nurses, nurses, and now it was silent—and I sat alone for six months, just completely incapable of going through her stuff or even functioning, really.

And finally someone sent me a 360, and the first thing I did was hook it up to my parents’ old TV and install Rez. And I remember exclaiming to the person who’d sent this Xbox: “Oh, my God, this feels so good! I caaaan’t belieeeeve how cathartic this feels!” And my mother’s dog, who was like 9 at the time, planted herself between me and the television and stared at me straight-on: “WHAT ARE YOU DOING, HUMAN.” Recovering my will to live, dog!

When you revisit a game like Rez, muscle memory takes over. It’s scripted, you know how the game goes, you’ve done this before, you’ve got this, and the feeling is just pure relief. It is as close as you can come to regaining any sense of normality.

Ted, my husband, has always warned people that I have a scarily accurate memory, from toddlerhood onward. He’s not wrong. So for me, games have always been a sort of mnemonic device. My life can be told as either a chronology of games I’ve played, OR as a series of painfully detailed moments. Or! A third thing: I can combine them! And I’ve found, as far as memoir goes, a spoonful of sugar means combining the two. Video games give me a pleasantly neutral lens for recalling the other moments in my life.

NNK: You have been treating games with respect—as fiction, as worthy of serious intellectual treatment— long before the banner cry of “games are art” became common. And in a different context, you’ve written: “We are all numbered; we are only here because we inexplicably believe games have the power to change art and literature and education and the world.” Do you still believe this?

JF: Oh ho ho! I remember the state of mind I was in when I wrote that, where I felt that, in the games industry, there are no real villains, right? To totally commit your life to this one thing—this thing with perilously little money in it, where, even if you excel, you will only ever have what is, in the scheme of all grand things, an incredibly small audience—all of this requires kind of a quirky, off-kilter, mad-scientist worldview. It requires a bizarre faith in the video games medium being somehow important, and here we all are, still figuring out how, exactly.

So yes, I’d always felt that anyone who is inexplicably invested in video games must be a friend of games, because there are so, so many other things in this life to dedicate yourself toward. Games are, like any religion, a faith-based pursuit. There is literally no other reason to recommend spending your life on them.

NNK: You’ve written that “there is something endlessly melancholy when a bit of software can do what you physically, emotionally, genetically cannot.” I’m thinking of your essay onCreatures, in which you write about saving Norns onto floppy disks to “freeze” them in time. Or in that previously cited review of Animal Crossing: at one point, you step outside and blink, and see people around you with their rich inner lives, just as in the game.

How can software help us see our surroundings more clearly, change our perception? It seems like you consistently argue that our relationships to technology can help us become more empathetic, compassionate; this muddies a very old (and tired) conversation on software and technology as inherently “inhuman.”

JF: It’s interesting, because it sounds like you’re asking about two different types of technology. There’s the inescapable kind that most people don’t even understand they have to preemptively opt-out of using, where everyone automatically has a Google+ account whether anyone wants one or not. It’s the “push notifications” and the advertorials and everything else I really hate.

And I’m not only talking about the erosion of privacy, here. We think of some technology as “inhuman” —and we think of it in those terms — because it commodifies humans, dehumanizes users, turns human beings into target demographics and unwilling content farms. We are all being “processed.”

But then there’s the other type of software, right? It’s the type you have to seek out, have to opt-in to. You mention Animal Crossing and Creatures, which are actually both types of “gardening” games, interestingly, but they’re also, just as you say, games about cultivating a fantastic and imaginative inner life. Or an incredibly boring, mundane interior life! Whatever!

And so maybe your question is sort of about the public, the artificial, versus the private and authentic. And that’s why moments like those I had in Santa Monica, where I had this window into watching a physical neighbor’s imaginary Animal Crossing house change and grow, are much more startling and intimate than reading a Facebook profile, I guess, with its whole constructed identity. (Obviously any player’s Animal Crossing house is also “constructed,” in its way, but it’s presumably just rooms cluttered with whatever junk makes the person happy.)

It isn’t too surprising that the real connective tissue among us isn’t Facebook profiles or Twitter-tweets but, instead, the parallel inner lives that we don’t really share with one another—share deliberately, I mean—but do occasionally glimpse. If the human condition is “every man is an island,” those moments of universal truth are the only thing to mitigate that hopelessness.

Video games often provide that. Or: they can facilitate those wonderful shared moments of recognition. They also offer a special language and lens for making sense of those moments. Games are a way of understanding that every human experience is equally important, that every experience matters.

NNK: What makes a believable, effective, powerful game world?

JF: Thank you for not saying “an immersive game world.” In the games world we tend to say “immersion” when we really mean believable, effective, powerful.

But if we were to say “immersion,” what we really mean is, how does a game concentrate on never “breaking the spell” of its particular reality? Usually the reality is broken when there’s any hint of uncanniness, when the seams show and the simulation makes itself obvious. Well, and that uncanniness could present as almost anything. If a character’s actions don’t quite line up with his dialogue, if there’s any ludonarrative dissonance there, that will break the illusion. If a character model is unusually dead-eyed (think CG Kevin Spacey), that’ll do it. If an object isn’t quite scaled correctly to its surroundings, like an unusually large flashlight on a comparatively small desk, that’s a “tell” that you’re trapped in someone else’s dream.

But you also have to decide, at the outset, what kind of universe you’re going to create. Will it be “closed time” or “open time”; is the Universe harmonious or chaotic? And what I really mean is, you kind of have to commit to whether you’re going to give your player the illusion of free will. You don’t HAVE to give a player “choice,” you know! You can just write a linear narrative. 2D platformers are linear narratives, laid out very much like comic strip panels: Move left to right, stage one, stage two, stage three, goal. The passage and chronology of ordered time is laid out spatially, and the player physically passes through that set order.

But if free will IS a thing you’re into as a game designer, well, any time a player senses that you’re behind the scenes pulling the strings, the player is going to get angry. Don’t tell the player she’ll be able to make her own decisions and then not let her. If the game is a sandbox game, don’t make one type of tree “destructible” and another type unbreakable. You have to follow your own rules. To return to Animal Crossing, that game is very clear about the rules, and the player is given absolute free will as “will” is defined within those boundaries and strictures.

What makes a piece of stagecraft ring authentic? How do you establish a believable sense of place? We know that, in video games, this isn’t necessarily accomplished with polygons or particle effects. You don’t actually need a lot of resources. With stage, you can do a lot in a black-box theater, this literal blank slate, and the question becomes more, well, how do we use this space, can we use it in an interesting way? Can we surprise the viewer?

It comes down to: are the rules fair to the player? And also, is the game never boring? Games don’t have to be “fun”—they can be torture!—but they cannot be boring.

![]() originally published at Rhizome

originally published at Rhizome